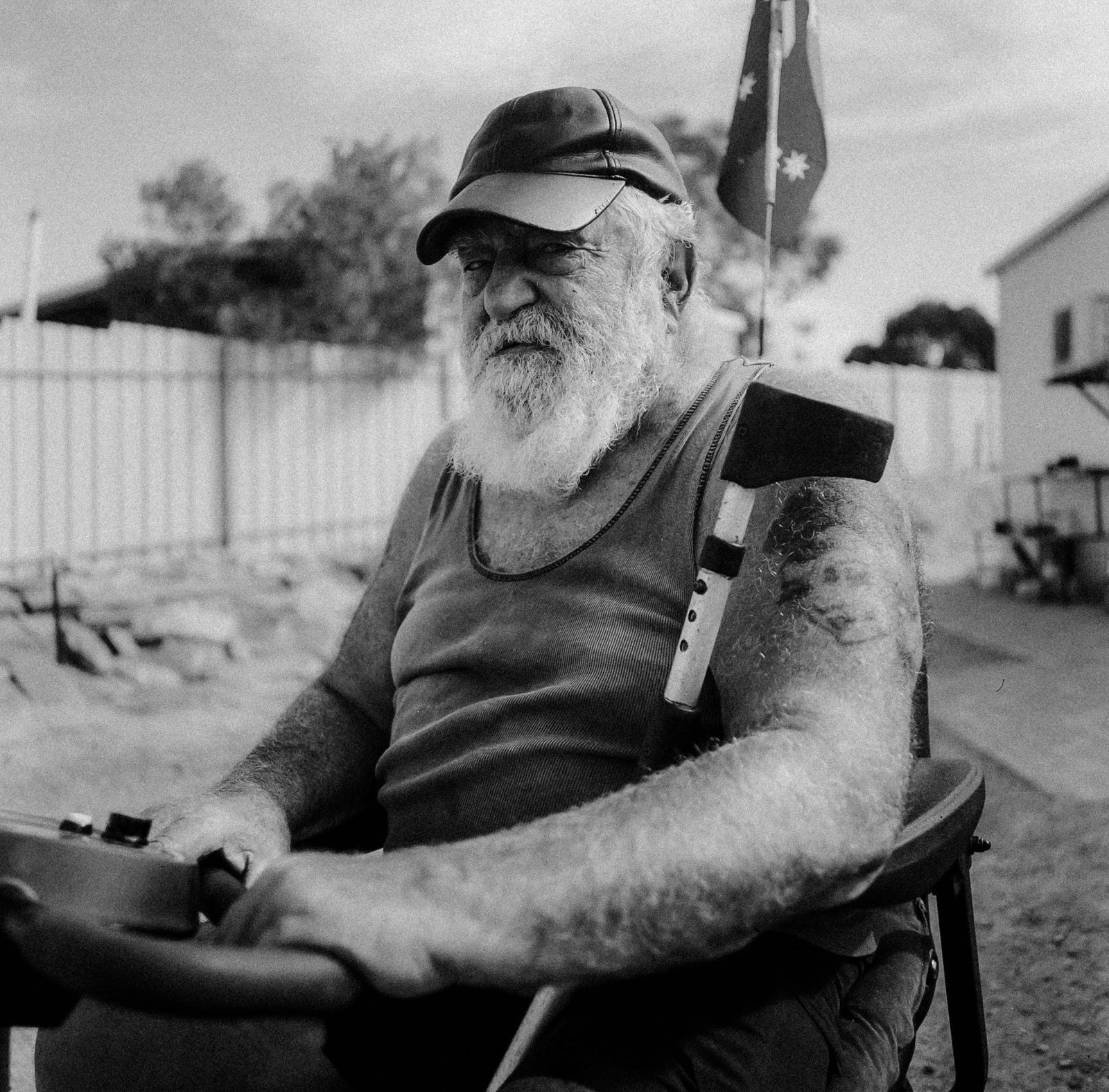

Matthew Thorne’s work is focused around the relationship between people, land, mortality and spirituality, in this case, a photographic documentation of community and land. His works are focused works that return a more traditional, chemical, and human element to the photographic.

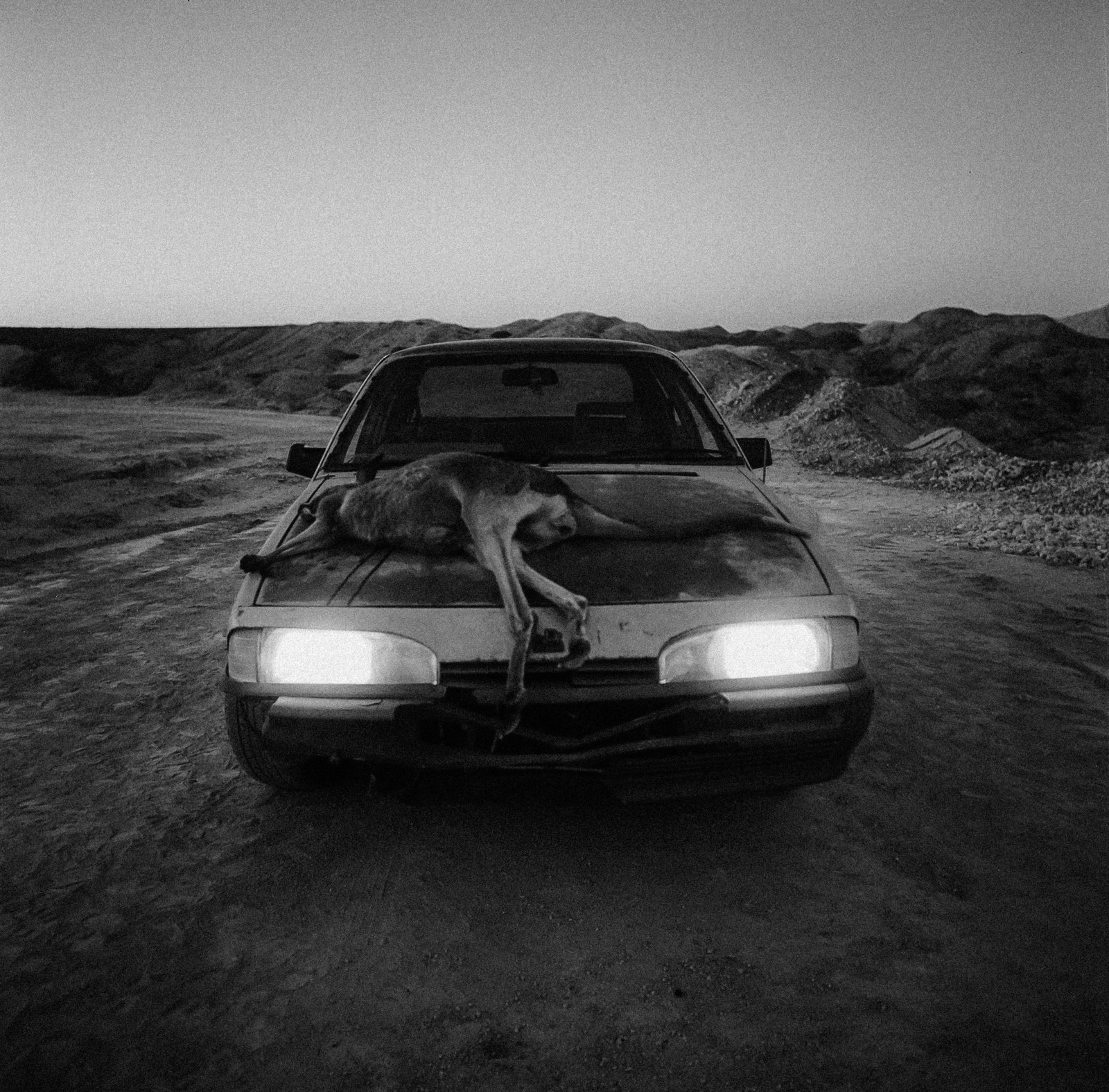

This work “The Sand That Ate The Sea” is a part of those series that came in conjunction with the making of a mythic film he wrote and directed in Andamooka. Andamooka has a great conflict within it – a conflict between the hard, realism of the working man’s world (and the unforgiving climate of the that land), and this innate magic of the endless horizon of the Australian red dirt. Desert Australians are a reflection of the land itself; the chaotic heat and vast stillness of the Australian desert is within them – forcing them to feel time in a different manner. Slowing their lives, and shaping their form. An Australian artist who grew up in the small Australian town, Adelaide. A sleepy, middle-america style town with a stillness like any other small town. On the edge of the desert, Matthew spent a lot of his childhood driving through the vast open space with his family. “I think something about that stuck with me. About the vastness of the land, but also that stillness. The endless horizon, and your place within it I think was something incredible to be exposed to as a child… but also something very magic.”

“I think the project was a farewell to my birthplace in a lot of ways. It was this goodbye to that land, and that energy that I knew – and also a farewell to my father and those lessons he’d passed on to me. I started writing the film 3 years ago, and I had this sense of wanting to tell a story based around sins of fathers falling to sons and about our relationship with time as people – and to invoke some of the mysticism of the Australian desert that I had known in doing that. And as I started writing this film, I began to find this idea of a recurring storm that would take the eldest man of a family lineage every 35 years or so… It came from a story my Dad told me at the time of how his father had died of a heart attack in a storm when he was a kid in Adelaide. And then – while I was writing the film, my Dad passed away very suddenly of a heart attack. And so I suppose some of that ended up in the film – part as goodbye, but also part as this informing of the meaning of the images and also the film itself. Something about the nature of time, of the cyclicality of life, but also what that means to the broader lives of that incredible community in Andamooka and their reflection of that. It’s a timeless place Andamooka, and it’s honestly something you can feel. There is a stickiness to time there, a morning in Andamooka is as long as a day in the city – feeling through that sticky medium of time was part of what I was trying to document, the stillness of a land unchanged for all time – and a land that was cared for and passed over by a 60,000 year old first nations people. A land where they now search for something (opal) that takes millennia to form, but is nothing but sand and water. The scale of time, and the relationship to the people (traditional, and new) was something I really could not let go of.

Then while I was making this film, and living in the community, I just felt like I needed to take photos of the people, and the land. It felt very private this place, something a little uncovered – like an uncontested part of the world. Of course it’s not! But there was something unique there, in the people – but also in the place.

In the mysticism of the opals themselves, but also this anthropological (or psychological) interest in what choosing to Opal mine says about people. What kind of people chose to move to the town at the literal end of the road. And then what makes living there so incredible. There was something interesting in that to me – and it felt very connected to my life, my childhood on the road and in the desert as a South Australian.

There was this real spirit to it – these strange connections that brought things together. I think these connections exist all around us and give as paths to take, point us down roads if we are open to them, and aware of them. They’re not grand in anyway – just these oddities: I’m born in October, my Birth stone is Opal – but I chose Andamooka to film (one of the main Opal producing towns in the world) without even knowing there was Opal mining there. I titled my script The Sand That Ate The Sea because it felt like it represented what happened to rain when water fell over the desert – and then when I was in Andamooka I found out that the whole town used to be an Ocean. It was following these things I think that led to the feeling and spirit that is in some of the images.”