If you go onto Google Maps, click the little yellow body shape in the bottom corner and zoom out you can see the areas of the world which are the most densely mapped. As you look at it, Iraq has, surprisingly for a country of its size, very few mapped roads or sites. This is down in part to almost continual conflict in the region (various coups, the gulf war, the Iraq war and then insurgencies from ISIL), but is also a reflection on how little we know about a country which is so often in the news, and which Western societies have significantly affected in the last few decades.

Charles Thiefaine first went to Iraq covering the liberation of Sinjar, a town close to the Syrian border, whilst he was a student. Once he had finished university, he decided to move to Mosul to photograph and work as a photojournalist. In photography, the allure of war has always been present. A photographer can work more lightly than videographer, but more-so the significance of moments cannot be overlooked through the still image. It is these moments that are so important to capture. War needs narratives, good, bad, victories, horrors, in order for the loss of life to seem justifiable. The moments captured through still imagery are those that will shape the recording of that time. What is lasting about Thiefaine’s work is not the images of war, but instead those of normality.

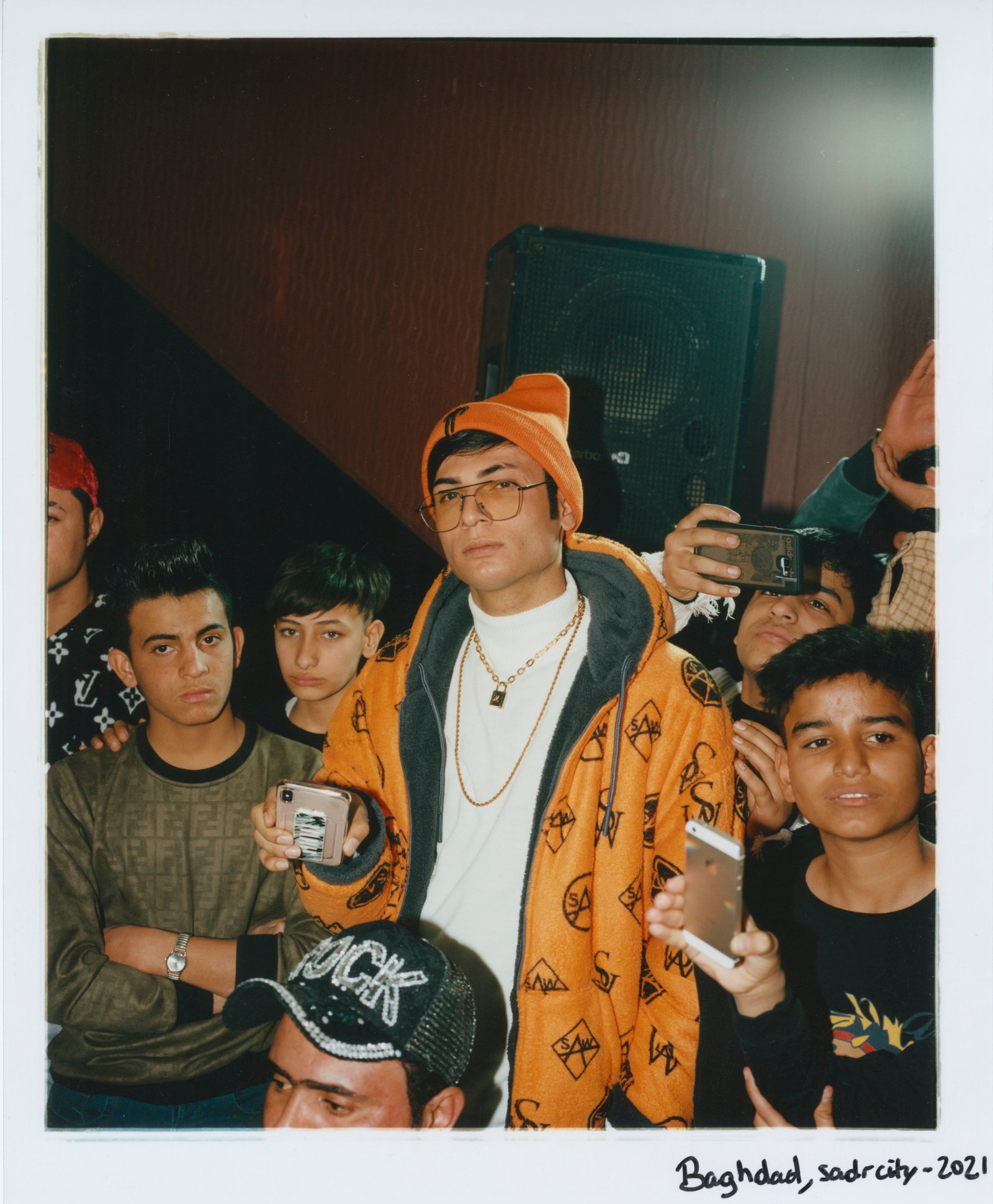

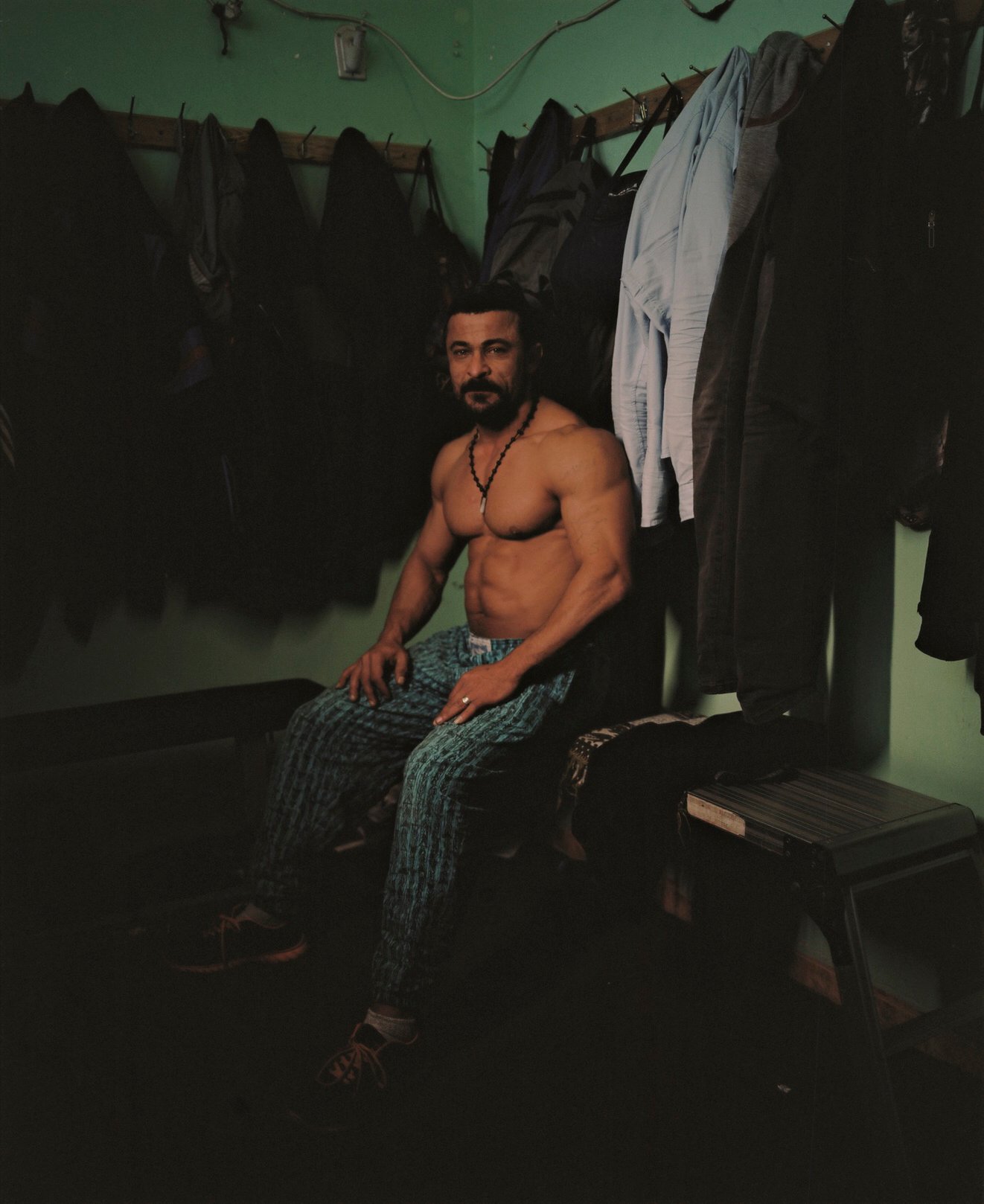

Through Allah-Ala, Charles Thiefaine’s work has progressed from that formation of documenting conflict into a much more richly tapestried cultural understanding. It is important to note that this is still the outsider looking in, but beyond that it is much more inclusive of the people he is working with to photograph. He came to photography originally through architecture - buying a camera to photograph spaces and models (this makes sense with consideration to his understanding of space and community) so it is slightly strange that portraiture has become a main tenet of his work. It is through these portraits that the work is driven. These are not the usual images from Iraq, from an embedded American or European photographer, working with peacekeepers or allied forces. This work is smaller, in a sense, as it does not directly follow the conflicts. In many ways, it is more important, following the smaller but constant movements of people within society. As Charles’ points out, it is important to not see it as a society with a fresh start, but that these cycles are somewhat a part of a development.

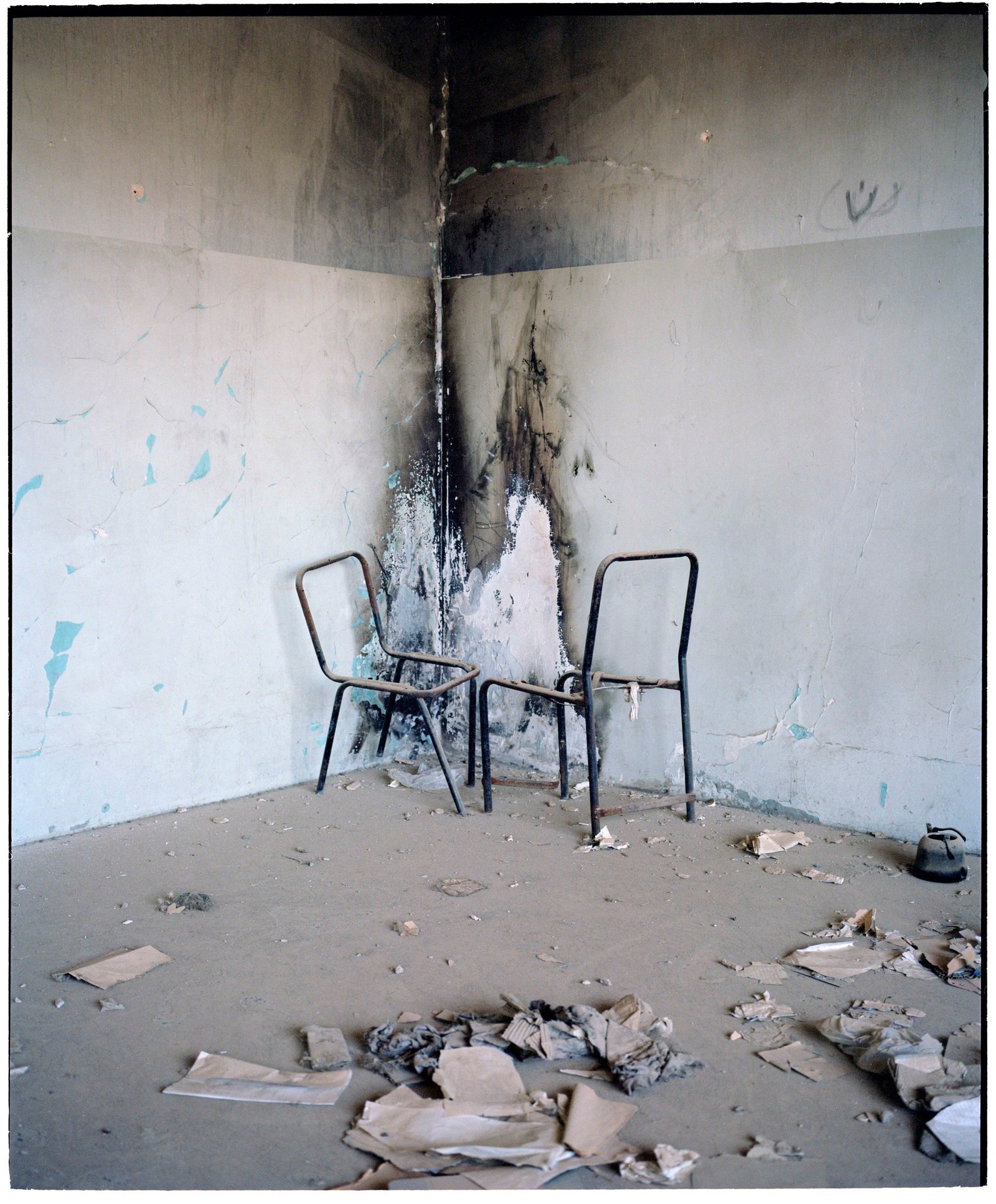

As he says during our email conversations, it is important for him that the images he makes to not betray the people he is photographing. His images reflect a personal experience of ordinary life in Iraq. When seen in the context of his broader practice he has photographed the conflict, and now the work is more closely linked to the aftermath, the people, and the rebuilding of structures. Many use his images of them on their social media accounts - to Charles, this sense of pride is really valuable in the images. It marks a hope not seen in many other images from the4 are. Only four years ago, Mosul was in ISIL control, in the North there are still sleeping cells of terrorist groups. Factionalism is rife, and one of the bigger problems in the rebuilding is that there is no one in real control. It is easy to see this through the images - buildings are now rubble, the scaffolds of encampments rather than building sites.

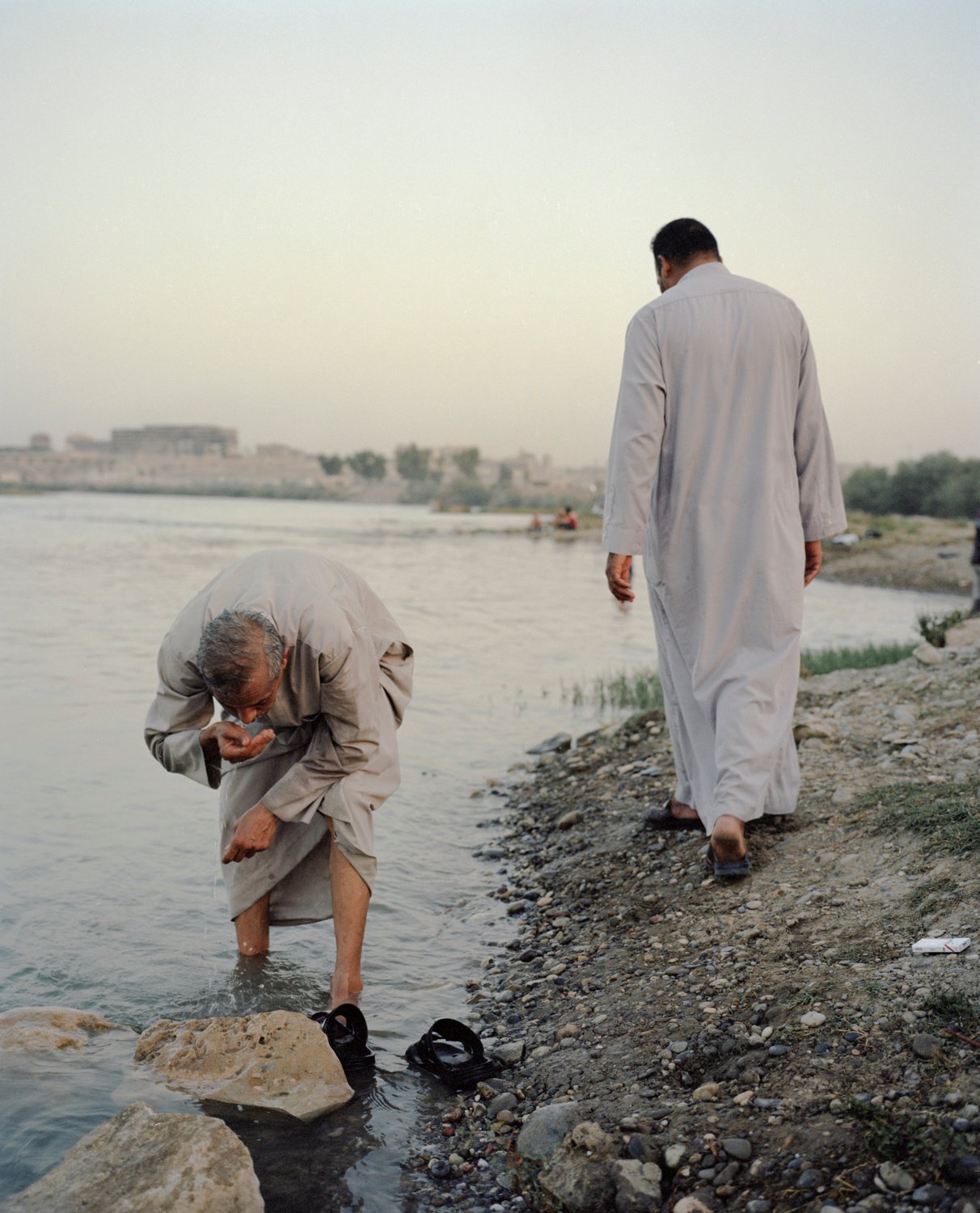

Whereas most of the imagery which comes from the area is of men: the fighters and the dying, women and children begin to feature more heavily through the series. Women in the area are becoming more involved with politics and are gaining more rights. Through the images, the children seem fairly carefree, a hopeful future for a country which has been continually torn apart. Men are still dominant throughout the series, but without the same machismo that has come to be portrayed through similar work. There is more of an intimacy and this series tries to steer away from the horrors, instead creating a new space within the narrative. That of small communities - people continuing in spite of the rubble. Without any solid governance (it was reported that when ISIL were in control, they were extremely efficient in governance) it is difficult to find a way forward. Despite the agitation for change which is going through the country, Charles’ says that many of the young people simply want to leave the country as they cannot trust the state. Officially the country is democratic, but everything is too fractured for one authority to control all of the various militias and groups. In 2003 during the invasion civic infrastructure was dismantled by the US, whilst also, more dangerously, all of the people with the ability to run the country were dismissed at the same time, creating this enormous power vacuum.

Through this more intimate portraiture of the space, Allah-Ala brings a different approach to the usually dusted down destruction of the area. Though this isn’t because he is necessarily intending to - it is because rather than the usual approach to the area from photography which focus on the conflict, Charles’ images come from a different place. This is a story about community, rebuilding, and the closeness of people. This is someone instead moving to a new place. The images are brought together through a rich tableau as much informed by learning about a new culture as it is about documenting the space during or after conflict. They are always conscious of the way in which each image maker is documenting their own narrative of the space around them. That said, Charles’ is much more hopeful, but also begins to reset the narratives of war to look not at the horrors, nor the momentary victories, but instead the far more poignant aftermath of the everyday.