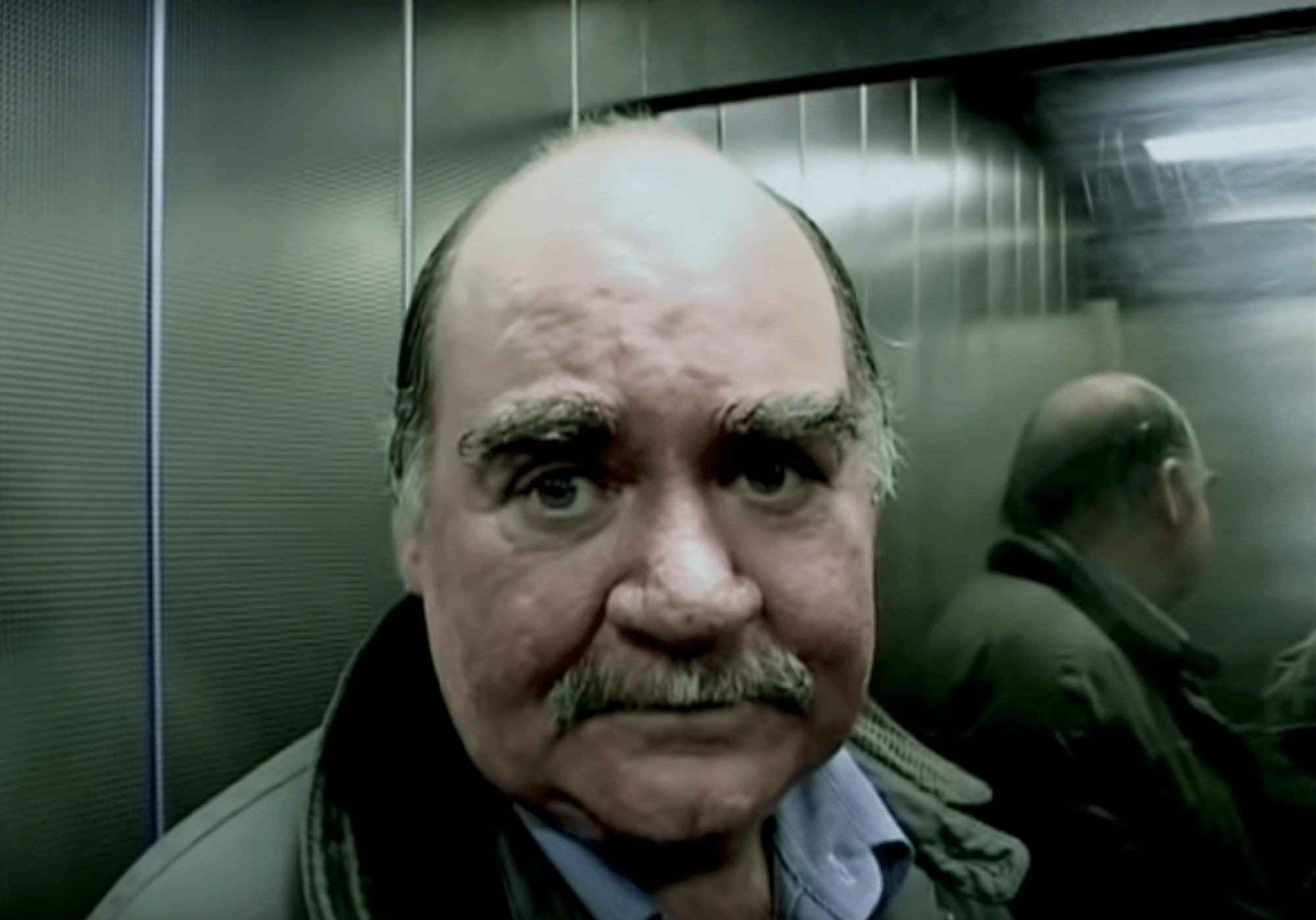

Julian Germain first met Charles Snelling in 1992. He has said that it was the brightly coloured car and house and the plants and flowers for sale in the front window that were “the reason I knocked on his door and we met.” It was the beginning of a friendship that also became an 8 year long photographic documentation of Charles’s life, culminating in 2005 with the publication of ‘For every minute you are angry you lose sixty seconds of happiness’, five years after Charles had died.

As I look through the book it feels motivated by friendship as much as by photography. The imagery appears informal, effortless and natural. Perhaps the pictures Germain was only occasionally making were almost incidental but what I see in these photographs is a true representation of Charles’s existence, without façade or impersonation. Germain observing and appreciating a simple man that had an ease and understanding of being. On a rudimentary level it is a record of human interaction – something quite ordinary – yet ‘For every minute…’ gradually accumulates until it becomes a description of the meaning of a person’s life.

Looking at Germain’s broader practise as a photographer, a common theme is his desire to cultivate relationships with individuals, groups or situations that he really cares about. He looks for ways to build something organically, with the intention for the people integral to the project. The ‘Classroom Portraits’ series is a very different body of work to ‘For every minute…’, documenting the varying conditions of school education systems across the globe as well as the children within them. But there’s a connection in the way that Germain strives to afford the incredible diversity of children and youth equal care and attention via a much more formal, yet realistic and respectful photographic process.

‘For every minute…’ contains minimal text, just a brief afterword by the author, but over the last couple of years (via Instagram) he has shared a little more information about the time he spent with Charles and about some of the pictures. There are some lovely anecdotes, such as Charles’s discovery of Mesembryanthemum seeds and Germain referring to, “the infectious pleasure he got from trying to say it.” These details add to our understanding about their shared experiences and relationship which seems wholesome and uncomplicated, and this feeling is profoundly reflected in the images. In one picture Charles is laughing in the front of his three wheeler Reliant Robin car and in another, a more vulnerable side is revealed as he looks through old photo albums of his wife, Betty, who had died a few years earlier. Germain is able to capture Charles’s zest for life, eating ice cream on the beach, or exploring the woods he played in as a child. The work doesn’t feel claustrophobic, it has a sentiment of freedom and meaning that becomes, in a way, liberating. The loss of Betty is deeply felt, but there is also the suggestion that this is accepted as part of life and that her absence is filled with the most simple of pleasures, such as growing flowers and vegetables, listening to Nat King Cole or looking at their old snapshots.

The design of the book couldn’t be more fitting, its 1970’s cloth bound floral cover and its dimensions matching one of Charles’s original photo albums. Opening the cover, the reader is instantly presented with the inside pages of the photo album itself, and I have the sense of having picked it directly from his shelf, an intimate and personal feeling. These photo album facsimiles make up more than 20% of the book. Placed at the start, middle and end they act as milestones, with Germain’s imagery interspersed between, giving the impression that his photographs have become part of Charles’s album.

Every image is placed with intent on each page and sequenced with care. On the left we see a photo by Germain of a framed photo on a wallpapered wall; a portrait of Betty holding a plant and looking into Charles’s Kodak Instamatic. On the right is a portrait of Charles holding up the same camera, looking into Germain’s lens. This simple interaction between images re-imagines a moment from their past lives and at the same time reminds us of what Germain has called, “the emotional value and shared cultural significance of amateur ‘domestic’ photography.” The slightly wonky framing of Germain’s whistling kettle or the subtly out of focus image of Charles escaping into his childhood wilderness each bear some resemblance to the authentic snapshots taken by Charles and Betty. It is these imperfections which breathe life into the work. The intention isn’t to be perfect, nor would that represent someone’s life accurately. Germain captures something of the essence of life that he must have felt from Charles and Betty’s photos and albums – and from knowing Charles as a friend. There is no battle or tension between Germain’s and their photographs; they sit together in harmony and this, for me, is at the core of the book and is something special. It explains, in a beautiful way, the relationship they had.

Published by MACK, 80 pages, 42 colour plates, 23.5 X 28cm, clothbound hardcover with 2 colour emboss.