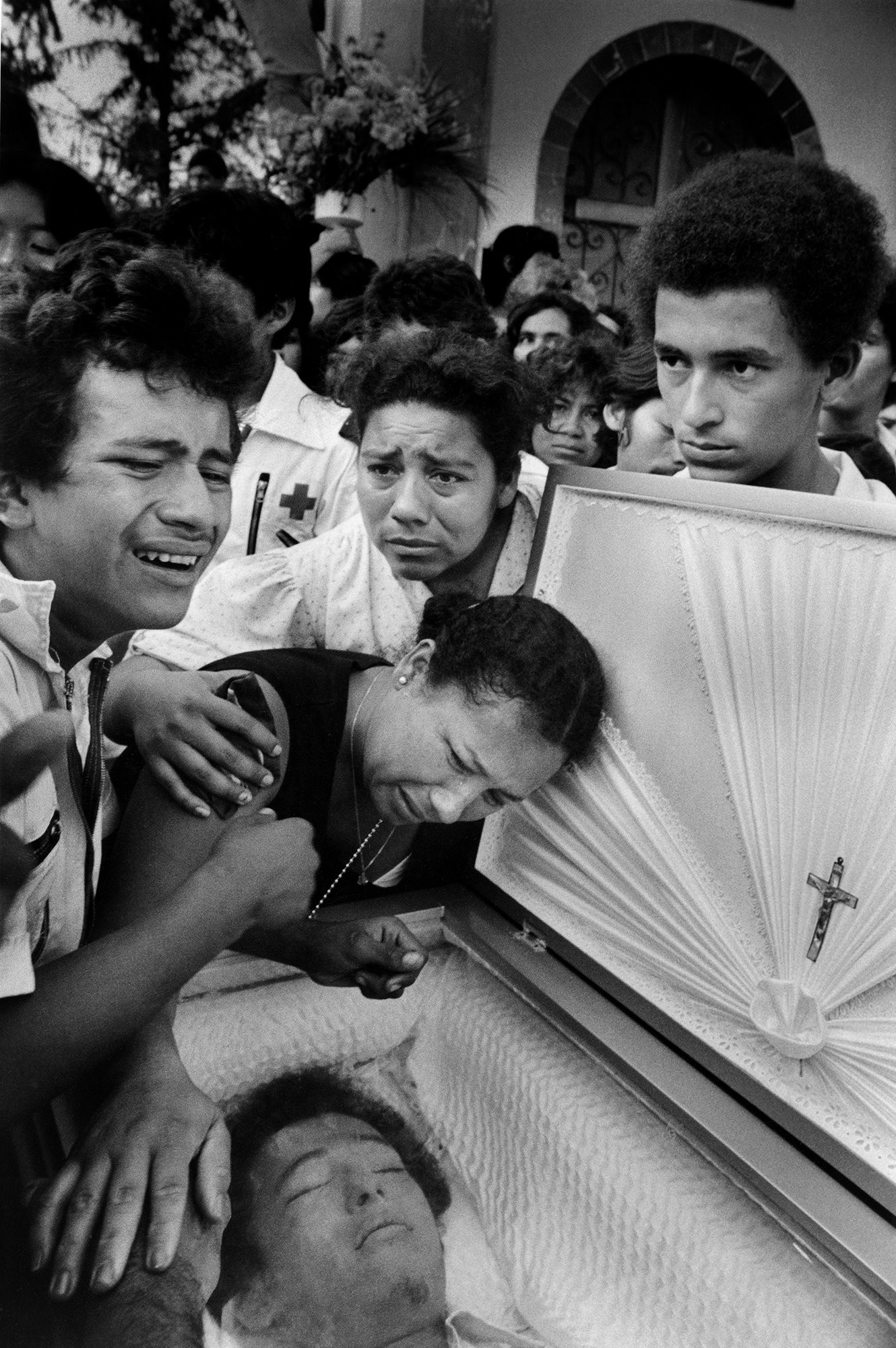

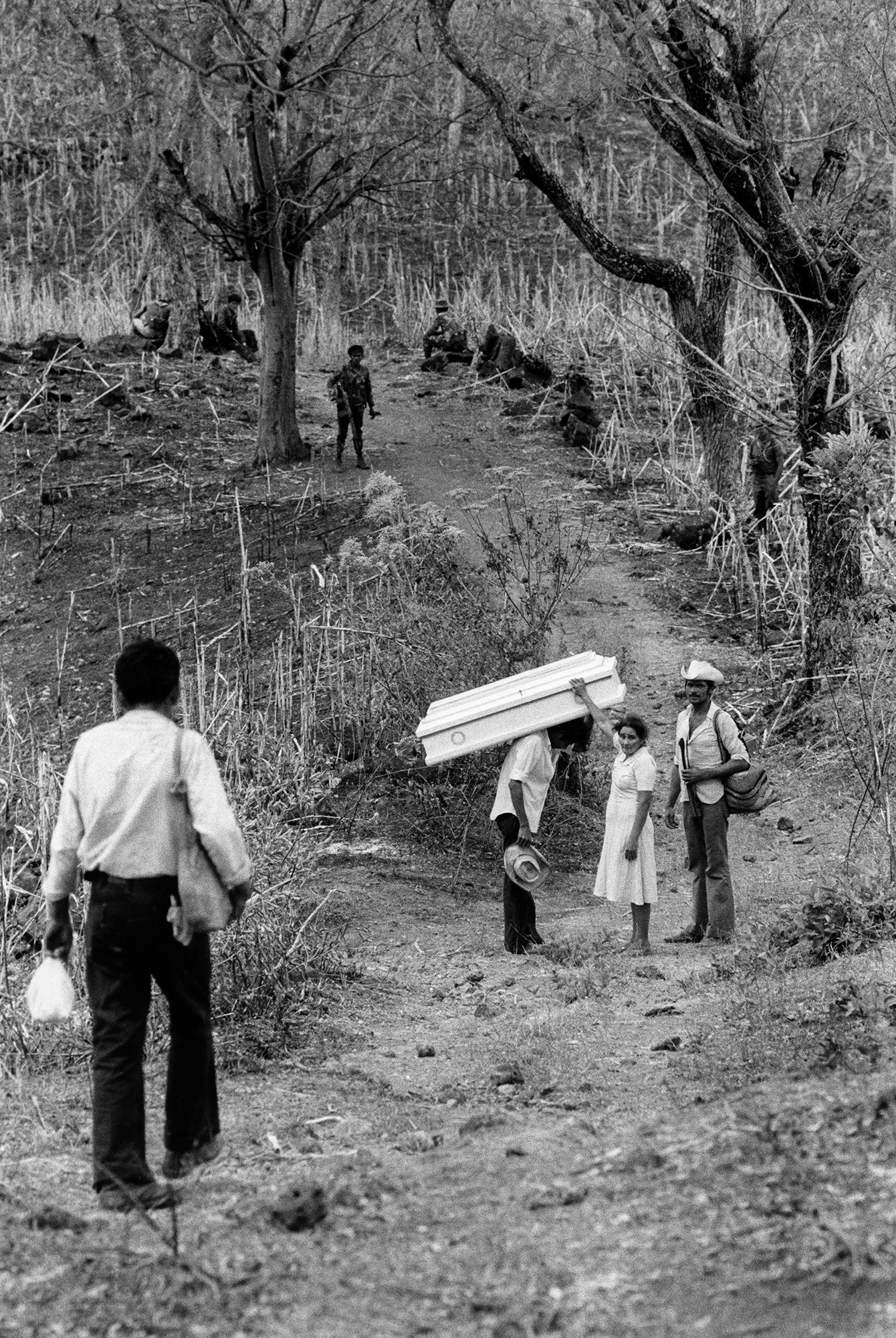

In 1984 photographer Mike Goldwater travelled to El Salvador’s northern province of Chalatenango to record the history of the peasant movement in the region and the role of campesinos in the Salvadorean revolution. These pictures, taken between 1982 and 1990 documenting the conflict in El Salvador, formed a one man show on tour in El Salvador and Guatemala, organised by Fundacion Latitudes, San Salvador.

As far as photographers go, you’ve had the opportunity to work on a lot of varied work over the years. How did you end up on assignments of this nature?

It was mostly personal choice. When a group of eight of us decided to set up our own photographer-owned agency, Network Photographers, at the beginning of 1981 there was nothing like it in the UK, only Magnum in New York and Paris. Our aim was to pursue our own projects in a mutually supportive environment, through our office sell our work, gain assignments for our ideas and make a living as freelance photojournalists.

At that time, there was a lively market for good quality photojournalism both in the UK – with newspapers and weekend colour magazine supplements – and in Europe, USA and further afield. All these publications had picture editors, then a well respected and properly paid job, and they had budgets to get the best material they could.

In 1980, before we set up Network, I made a self-funded trip to Vietnam to do a story on Agent Orange – showing how aerial spraying of a highly toxic defoliant by America on the Ho Chi Minh Trail along the Vietnamese-Cambodian border had caused birth defects in families of Vietnamese soldiers who had been soaked in the chemical. The story had taken several months to set up but my set of pictures became a cover story and 13-page feature in a Dutch magazine and was published widely elsewhere.

I was keen to do more international photojournalism. I made my first trip to Central America in the spring of 1981, initially to do a story with the Guyami Indians in Panama who were resisting plans by Rio Tinto Zinc to turn a large part of their traditional land into a vast open cast copper mine. It was a strong story. I started with RTZ to get some images of the beginning of their mining operation before working with the Guyami community. It was almost at the end of the trip, while leaving a Guyami gathering held in a clearing in a remote forest where RTZ were planning to build a hydro-dam to power their copper smelter that I got arrested by the Panamanian police.

There had been an argument between the Guyami leadership and a government official who had arrived at the gathering by helicopter. Me and my travelling companions from a local solidarity group were all interrogated separately. All my things were gone through. The police wanted to confiscate all the exposed film I’d taken on the trip.

To save space, before leaving the UK I had unboxed all 200 rolls of colour and B&W film and put them, 50 rolls at a time, into clear plastic bags. The exposed rolls were all numbered and had their tongues wound in, the rest had their tongues out, but through the plastic bags it wasn’t that obvious. I handed the policeman a bag of 50 rolls of unexposed black and white and managed to persuade him that these were the ones he wanted. We were released the next morning back in Panama City. I had enough material for the story and was determined to leave the country before the black and white films were processed and discovered to be blank. I spent an anxious few hours flushing most of my notes down the loo and I managed to get a flight out to Miami that evening without incident. The story was published in the Observer magazine and elsewhere. As it happened, the copper price dropped shortly after, there were changes in the Panamanian government – and RTZ’s plans were shelved.

On the way to Panama, I’d stopped in El Salvador and Nicaragua to do some short aid agency assignments. In Nicaragua, the Sandinista revolution two years before

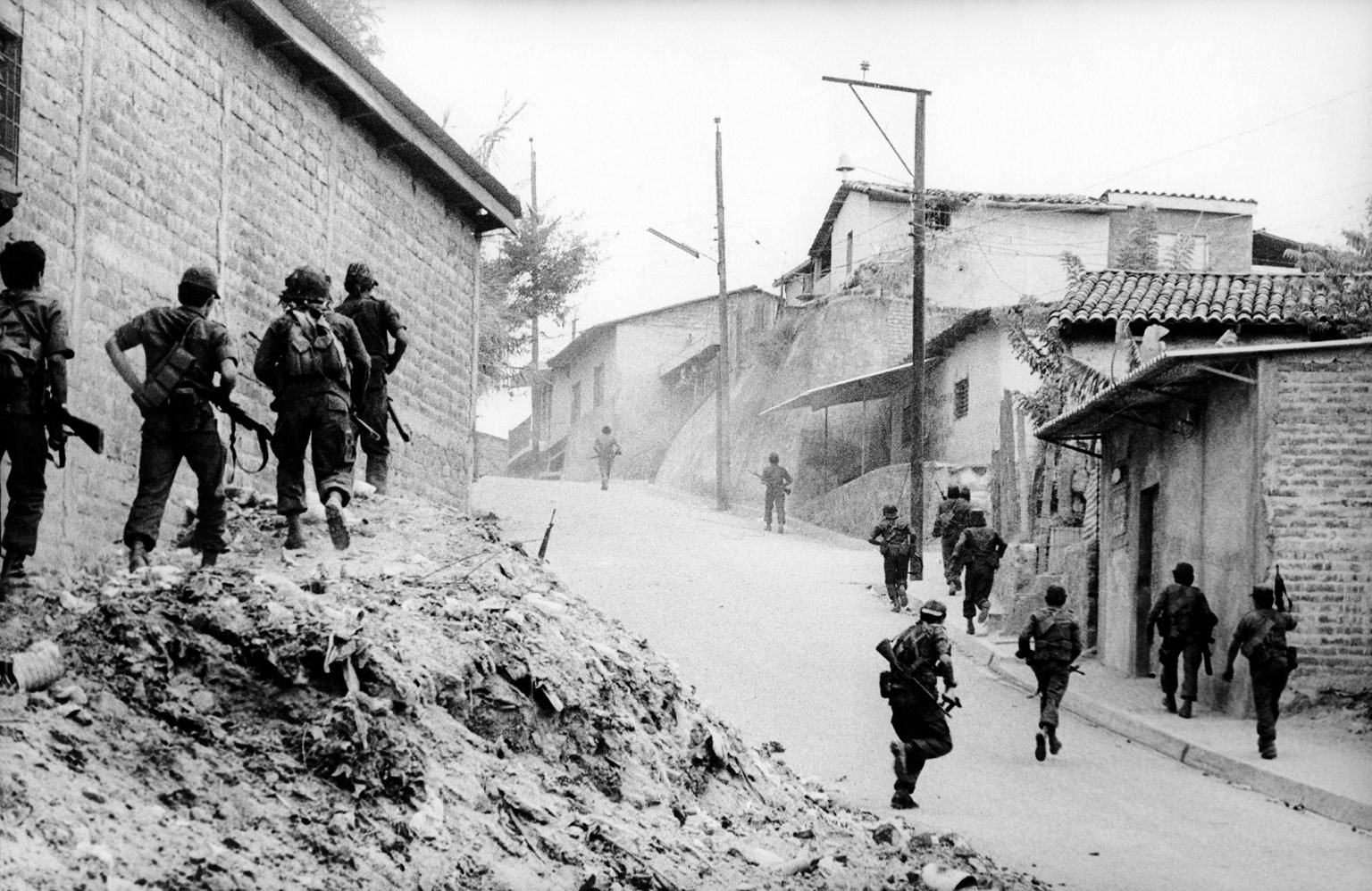

had overthrown 43 years of autocratic dictatorship by the Somoza family. The USA under President Regan was determined that revolutionary movements that had sprung up in El Salvador and Guatemala should not be equally successful. The region was a tinderbox. The conflict in El Salvador was brutal and it wasn’t hard to see that the USA were backing a very repressive regime. Meanwhile, in these early days of the Sandinistas, Nicaragua was an optimistic place; huge literacy and healthcare projects were underway across the country and international solidarity movements in Europe and the USA were sending young people to help pick the coffee harvest. The contrast could hardly have been stronger. It was clear that the region was going to be a geopolitical hotspot for some time and I was keen to try to cover the events there as they unfolded.

By the time a peace deal was finally signed in El Salvador in 1992 I had spent more than two years in the region.

I’m interested in the fact you documented the Georgian Civil War in colour and this series in black and white. Do you feel there was a darker side to this project in particular and felt it needed to be documented in this manner?

Sometimes these decisions are more pragmatic. In both 1982 and 1984, I spent nine months at a stretch in Central America, much of it in El Salvador. To sustain me on these long trips the Network office would arrange assignments with a range of clients and some, like The Times in London, wanted black and white material, while others, like Time or Newsweek magazine, wanted colour. UK aid agencies – Oxfam and Christian Aid amongst others – generally liked to have both. The picture library at Network was happy to have both colour and B&W material. I would make a weekly airfreight shipment of unprocessed film to London or New York.

I would often be working with three cameras, all with prime lenses, one for Tri-X, one for Kodachrome 64 and one with faster colour transparency film for interiors. Trying to capture an in-depth story in both colour and black and white had its frustrations; I became quite adept at switching lenses between cameras in fast-moving situations but inevitably there were times when you put down one camera to try to capture a similar moment on the other film stock and actually missed the best moment. (One of the advantages of modern digital photography of course is that these issues need no longer arise).

With colour, one practical issue was the narrow exposure latitude of colour transparency film – a quarter of a stop could make the difference between a perfectly exposed slide and one that was out. Along with others shooting transparency, I would carry an incident light meter in the top pocket of my camera vest and would take a quick reading before every colour exposure. In the early morning and late afternoon the tropical light of Central America can be magical. But after 9.30 am and up to about 3.30 pm the brightness of the light exceeds the two stops between highlight and shadow that transparency film can handle without using fill-in flash. Even used with great care, fill-in flash can have a certain look and in conflict zones it is not always appropriate. Trip a flash and you can risk attracting attention to yourself and others. Black and white film, however, has a seven stop exposure latitude so it’s possible to shoot through the day without that particular issue.

It was always a relief to be able to shoot a whole story in one medium. For the story on Georgia, I put up the idea to Colin Jacobson at the Independent Magazine as a colour story. And that was how it ran as a cover story in the magazine.

Certain things seen within your images are things that the majority of humans and especially photographers don’t ever witness within their lifetime. Do you think witnessing the things you saw in El Salvador changed your perspective on photography?

I was self-taught in photography, I didn’t study it at college, I did a BSc degree in physics at Sussex. In my early 20s, before Network, I spent six years at the Half Moon Gallery and Half Moon Photography Workshop (HMPW), and was one of the founders of HMPW’s magazine Camerawork. The magazine in particular tried to raise issues around the politics of photography and the responsibilities of photojournalism. Tom Picton, photographer for Time-Life and lecturer at the Royal College of Art as well as also being one of the founder members of Camerawork, was very good on these issues and I learned a lot from him.

In the series of six Camera Obscured? seminars on photography that we set up at the Half Moon Gallery in 1975, the one on ‘The Task of the Photojournalist’ left the strongest impression on me. We invited Philip Jones Griffiths to host this seminar. He had just published his book ‘Vietnam Inc’ and we used Philip’s original book page layouts – twice the size of the book itself – as the accompanying exhibition in the gallery. I think this book remains one of the most powerful photojournalistic books ever produced. While some photographers tried to be on the cusp of events as they unfolded, Philip took a more political approach, choosing to put himself both with troops on the front line and at places where decisions on the progress of the war were being made, making powerful images all the while. It was a strong reminder that in conflict, images of action alone are not enough.

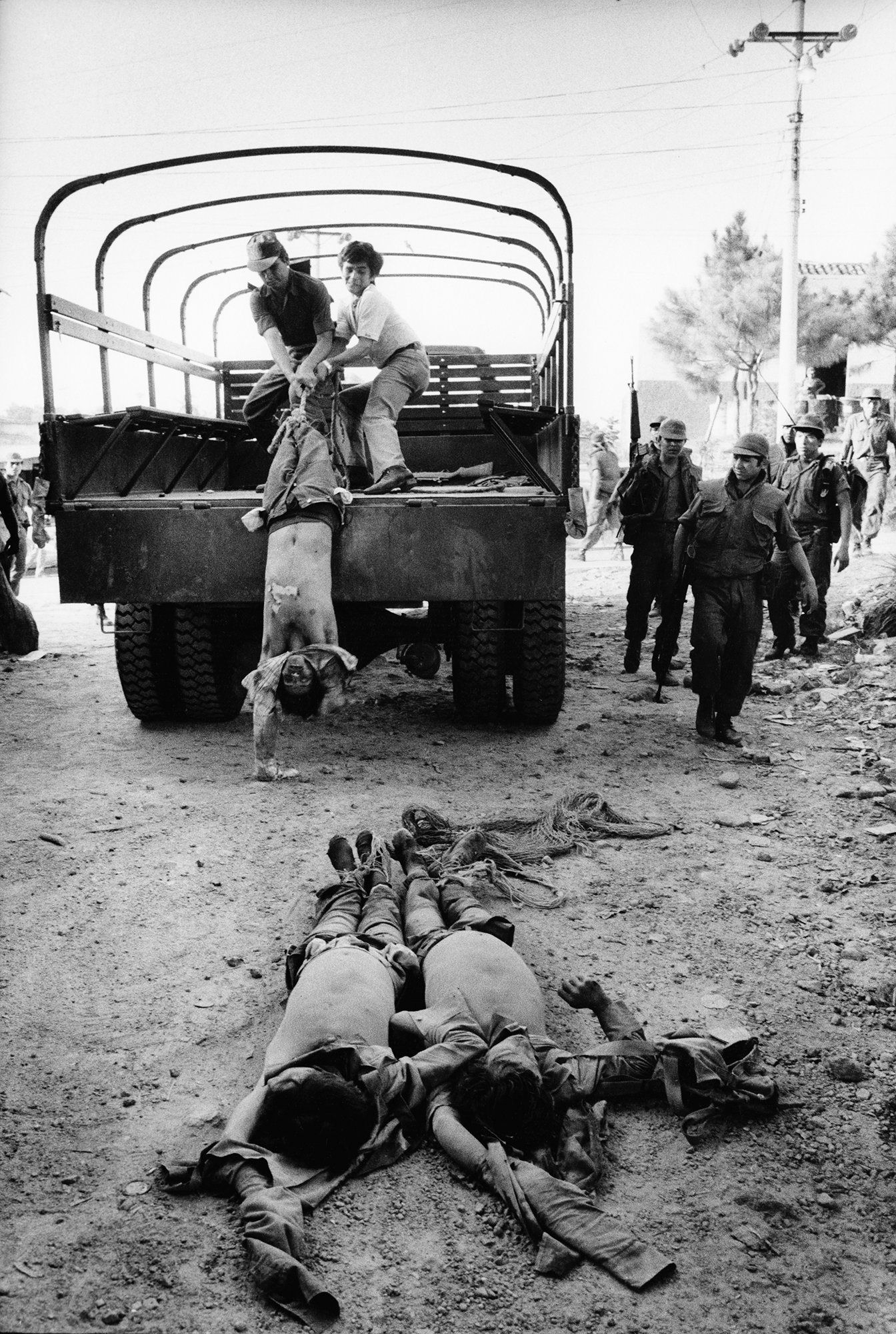

As a photojournalist, I think one has a responsibility to be as well informed as one can about the situation you’re about to put yourself in. You bring this subjective knowledge into the way you work and this helps you to decide where to put yourself and how to frame what’s happening in front of the camera – to try to make some comment on what you’re seeing – often to try to honour in some way the oppressed and highlight in some way the hypocrisies of the oppressors. In the more extreme moments in El Salvador, I tried to hang on to these ideas and put my energies into trying to make the strongest images I could. I think this helped me through it, rather than trying to produce ‘objective’ images. In reality, there is no such thing as objectivity in photojournalism.

Do you feel you’ve become desensitised to war photography?

No – there are some amazing images being generated right now that move me – for instance in the present uprising in the USA. There remains a hunger among photographers to bear witness, to document injustice and conflict, in the eternal hope that their work will somehow make a difference, and just occasionally it does. Amongst many others – Ivor Pricket’s set on the battle for Mosel in 2017 was extremely powerful, as is the work of Moises Saman across the Middle East. Anja Niedringhaus, killed while working in Afghanistan, produced some amazing images as did Tim Hetherington, a member of Network for several years, who was killed covering the conflict in Libya. At the end of last year, Mathew Abbott produced an amazing set on the bush fires in Australia – no less dangerous because there were no bullets flying.

Within the series, you spent time with both the El Salvadorean armed forces and FPL troops. Did you feel a conscious sense of support for either side?

Many of the soldiers in the Salvadorean army had been conscripted into service and were there under duress, and you could only feel some sympathy for them.

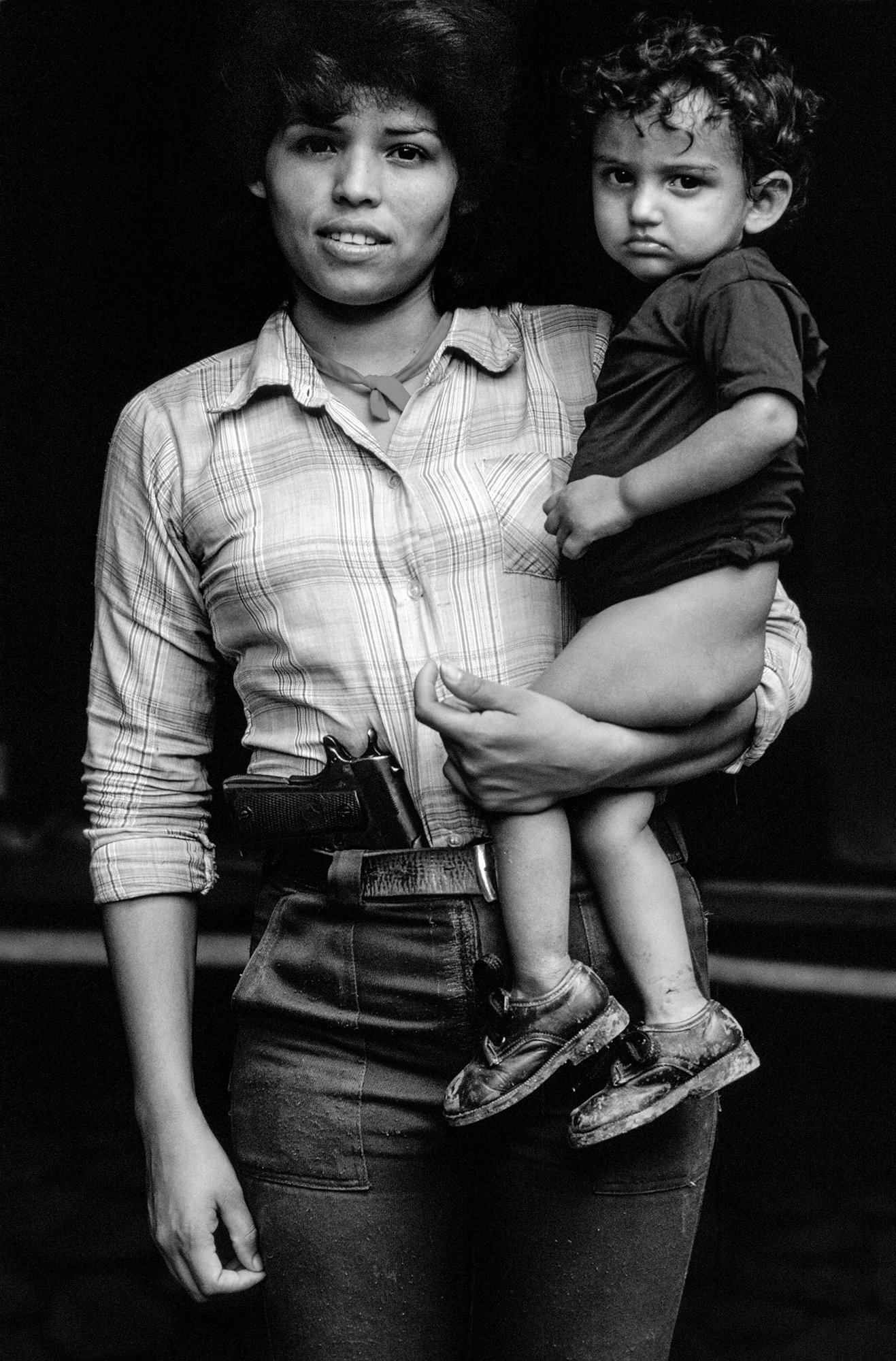

However, the rebel movements in El Salvador had sprung up, not just under the inspiration of the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, but because of years of corrupt and repressive governments in their own country. I, along with many of the other photographers covering the war, felt supportive of both the peasant farmers and the rebel movements that aimed to improve their lot.

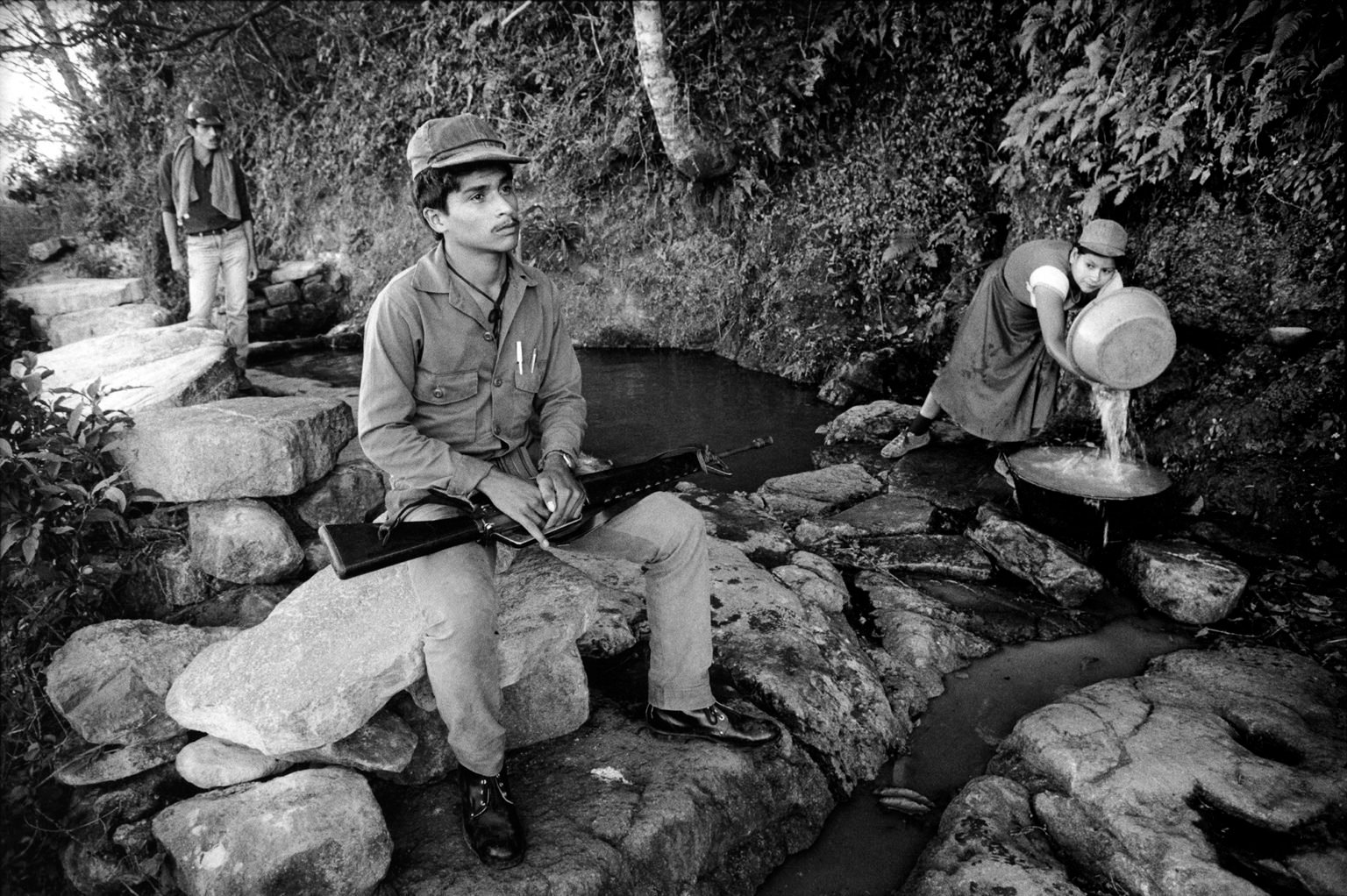

I was curious to document life in the guerrilla-controlled areas of the country. It was a complicated and quite dangerous process changing sides and in 1982 I made a brief trip to the FPL area with an aid agency person. I felt I only scratched the surface on that trip and in 1984 – in a trip that took nine months to set up, and involved a number of clandestine meetings in the capital, and dressing as a Mormon missionary to get through the last army checkpoints – I and an academic expert on Latin America, Jenny Pearce, spent two months within the FPL zones of control. What we saw and heard reinforced the sense that the peasant war was just.

In 2014 I went back with Jenny to follow up on some of the people I had photographed in the guerrilla-held areas of El Salvador, particularly in the area of Chalatenango, which was a powerful experience. While many had been killed a surprising number had survived. The FMLM, the umbrella organisation for what had been rebel groups, including the FPL during the war, was then the democratically elected party of government. I had an exhibition of my photographs of the war in San Salvador. Jenny’s son Richard Duffy came too and Richard and I made a film ‘The Past is Not History’ with some of the survivors. The film is on my website.