Matthew Finn has spent a predominant portion of his life photographing people. Primarily the members of his family which are closest to him. Over thirty-plus years of shooting he has amassed work surrounding relationships with his mother, uncle, wife, and son, as well as countless others. Over a few months, I spoke to him about Mother, as well as Wife, their differences, and how they relate to one another. By chance, I had also bought my Mum Mother earlier this year, so spoke to her about what she thought about the book, both in the context of being a mother but also as someone who is a palliative care nurse and has written care plans for those diagnosed with dementia.

I was first lucky enough to see spreads from Mother whilst sat having a pint at a repetitively brown table in the Derby Premier Inn (or perhaps a Travelodge). I was still at uni, and it would have probably been the first time that I would have seen a proper photographer's work before completion. Perhaps it is especially because of this first viewing that I have always found myself having a slight attachment to these images. Even as loose spreads, viewed through a veil somewhere between slightly and very pissed, there has always been something about the images, (and more widely, Matthew’s work) that have a captivating and stark quality.

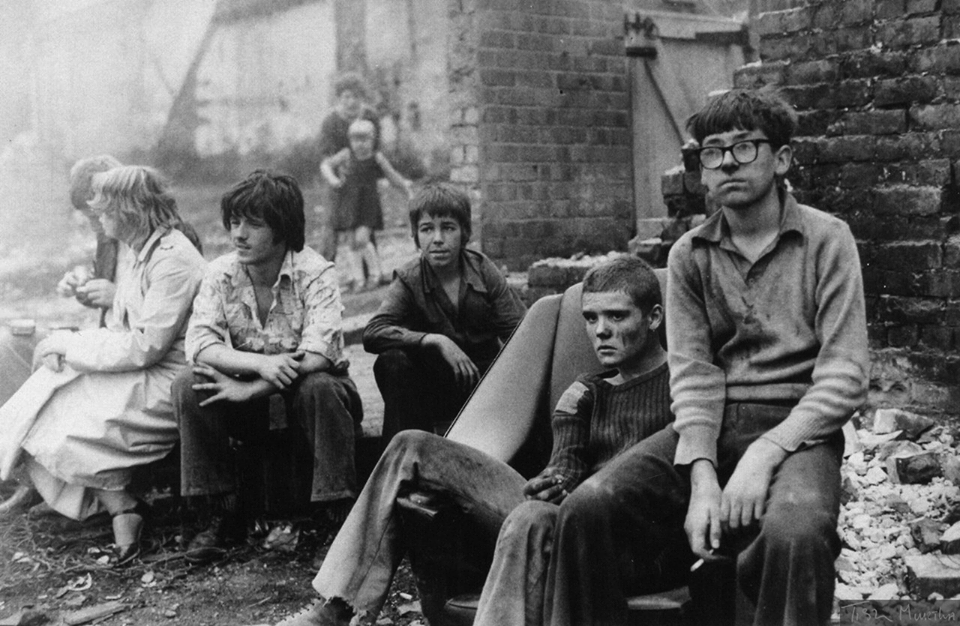

A slowness etched into the images is the first thing you notice. Whereas changes happen in an instant for the viewer compared to the photographer, the changes a person undergoes are so much more focused in Matthew’s work and are imprinted into every image. As with most things shot a few decades ago, the domestic setting no longer feels quite as intricate as it once was. Many homes now seem to share a very similar semi-minimalist flatpack decor. The home as a domestic space had a much more developed facade, with an orderly nature to how a home should look, and Jean’s doesn’t seem to be an exception to that. Small intrusions of untidiness in the space look more to be caused by Matthew and his uncle - videos strewn across the floor, a newspaper on the sofa arm. The lack of distraction in these images adds only to the focus and then the development of these continual portraits made of the family. It is quite telling that each subject has their own book, and are seen as separate bodies of work. It could so easily be tempted together into some sort of amalgamated family album; Matthew’s resistance to this allows it instead to become the study of individuals, though from a unique perspective, and they can be viewed either together or as separates.

Matthew’s practice began in formalism, looking at images by the likes of Lee Friedlander. This is very easy to see in the small pieces of his early street photography; though it carries over to the images shot in the home. The obvious main formal element is that almost exclusive devotion to black and white. Black and white photography is primarily related to the context of truth, though also allows the photographer to hold complete control over their process. From development to printing it can all be done with relative ease in your own home. This choice is somewhat more reflective though - in many instances, the making of this body of work with his mum was a form of communication between the two. They were never a touchy-feely family, and this collective action would almost stand-in for those moments. On reflection, that holding onto the film and then also process feels more personal, part of a larger process in the creation of the work for Matthew than simply the making of images. Those formal elements make up the work (as well as Matthew’s wider practice), but the body itself has gone far beyond that initial formalism, becoming a form of collaborative communication.

A part of this process was that she would always see the prints - they would be left hanging to dry throughout the house, impossible to miss. The print is an essential part of this practice - where practitioners now (myself guilty of this at times also) can be in the habit of shooting and then scanning. We often lose the practice of looking. Printing forces you to engage with your work as a process of single images. They carry a character, they are no longer motionless keyboard movements. It lends itself to Matthew’s practice especially - durational work gives the time needed to develop work image by image. Photography as a wider art form now feels much more instantaneous and reactionary - the crush of digital has been to push for everything to feel like it should be quick. A habit has been formed in which the act has become a reactionary process, so it is always refreshing to see work where it is no longer the case, and instead, the images are given the time that they need.

Matthew is one of a few practitioners that finds patience within the process of image-making. His portraits are traditionally formed in that hinterland of conversational distance - focused on the head and shoulders, chopping off the body at the thighs. This distance is telling of the way he works with a subject - the making of images is a part of a conversation and it follows the engagement between two people more than it does any aesthetic want to photograph them in a certain way. It is this distance that gives them their intimacy - the viewer is automatically in the frame as a part of this conversation, but foremost it follows a naturalistic way of photographing someone and them being at ease within the image. A truer portrait of a person.

When you are learning and developing a practice there is no real thought given to the notion of the subject and the muse, and this probably isn’t a question in the early Mother work. As his portraiture has developed, this is something he has thought about a lot more, and as someone who has photographed women a lot, there is a large notion of that which begins (more obviously in Wife) to look at that male/female gender imbalance in image-making. This theme continues through Wife, beginning to question whether a man can photograph a woman without the trappings of that balance of power.

There are stark differences between images from Mother and Wife. Not just in the sense that they come from different periods, but in that what is gained in awareness of the image and the use of it is lost in a naivety towards the camera. There is much more awareness in Martina of how the image will appear, and this shows through the way she acts around the camera. The pacing of images of her is much more staccato. His mother was more often than not a willing sitter, natural in the pose but acting up to the camera slightly. Images of Martina are much more offhand, captured, stolen. As someone who photographs my partner, the images seem to carry the movement of the exchange, and in some much of the same half forced relinquishing expression that is recognisable in Matthew’s images of Martina.

Even since beginning this body of work, the photographic image has taken a transformation. It has become almost throwaway. The gravity of the image has been lost slightly (though on the other side there are arguable benefits). Whilst my mum photographed her mother holding the now lifeless body of my grandfather, my grandmother told her not to put it on Facebook. Now that images have become ubiquitous, is it so that we have lost these boundaries. Matthew’s work itself has always pushed those boundaries - what is it okay to photograph, what is it okay to publish. There is more gory work out there that speaks more directly about death, but in Matthew’s case, this balance is caused by where to draw the line with that emotional connection and how the photograph can justify it. Probably to an extent this tentative nature is probably passed along from being part of a family who didn’t talk about death or heavier subjects, and therefore those boundaries are ever more present and tangible.

With each flick through the pages of Mother, the narratives change, There is something beautiful in the photobook that no other art form (in my opinion) can reflect. You attach yourself more heavily to different images every time. It responds to the viewer's feelings and fears intimately and therefore can change with their feelings, especially in a book like Mother.

As much as Matthew never wanted it to be a book about dementia, and a reflection of both the person going through it, as well as their family going through this, to many, it will be. Within the first read, it is easy to be pulled into this narrative - many of the heaviest images are near the end, and as we learn more about Jean, and delve into her life over the years we are hit emphatically with the crescendo of her deterioration. Many of the most brutal images, Matthew has kept back, to ensure that the work does at least have some separation between the documentation of dementia and the documentation of a loved one. Jean slipped at her sister’s house, broke her hip, and began suffering from delirium. At some blurred point, she became unable to recognise him, slipping into paranoia which meant an end to make images together. As this slipped, she began routinely thinking that Seb, Matthew’s son, was Matthew from a former time. ‘Mixed dementia’ was the pronouncement on the death certificate in 2017.

Dementia is often overlooked - seen as an illness that usually accompanies the end of life, though does not necessarily end it. It is one of the illnesses which still scares many - it is a blend of physical and mental illness breaking down the entire body. In comparison, it seems easier to understand someone developing cancer or another disease. We understand the physical more than we do those that affect the mind. Dementia, in the earlier stages, tends to be accompanied by delirium. This affected Jean after falling and breaking her hip. Suddenly family were not friends, she found it hard to trust people and no longer recognised them in the same way. Previously they had planned to move her into a flat below her sisters, on the ground floor, but this became untenable after her fall. She could no longer look after herself and subsequently spent her last three years in a care home. The most difficult part of losing someone to dementia must be that they are still there, but no longer present in the same way. Through the images, it is easy to recognise a slightly more glazed-over expression in Jean’s eyes as time goes on.

‘Jean, I think it is’ said my mum, trying to remember her name, as we started talking about the book. She has worked in palliative care for almost 30 years and contributed to writing on how to broach end-of-life care for dementia patients and their families. I ask who she sees in the final images of the book, and she emphasises the fact that she 'wouldn’t want to see a dementia patient’. Part of the problem with dementia is early signs are easy to miss or misdiagnose and not recognise, and then there is a latency in the medical profession in being honest with families early enough. Partly this reluctance comes from that aforementioned difference between the mental and the physical but also being seen as just memory loss. It is much more than that - it is a sign of a decline in brain functions. Delirium can accompany this and is a heavy confusion. In Jean’s case, it seemed likely from what Matthew was saying that she was showing early signs of dementia, which then worsened after her fall cause delirium (a more aggressive form of confusion). Dementia which had possibly already been present seemed at times more related to a reliance on Des, becoming more apparent after he had died in 2017.

Despite dementia being a large part of Mother, the more time you spend with the book, the less prevalent it becomes. Strangely, it almost has a backward narrative - those images of finality offer the astute access point to want to know more about who she is. The more you begin with her dementia, the more you delve towards the person she once was. A protective nature hangs through the images, a reflection of their relationship. Matthew’s childhood was unusual in that his father had many other families, something he never found out until his father’s funeral in ’94. Throughout his childhood, his mother and uncle lived together, his uncle filling out most of the role of his absent father. Matthew would regularly see his car outside other homes, only to be told he was mistaken. Though they were not together, his mother and father would occasionally go out together. She would routinely be stood up by his father. Seeing her, waiting, after dressing up and making herself up, only to realise that he wasn’t coming, and then having to go back upstairs to get undressed again into house clothes, returning to the living room feeling somewhat dejected. This has fostered heightened care towards her from Matthew. As they were never a touchy-feely family, they never really spoke of their feelings - or more about their situation as a family. Despite this, Matthew’s collective work on his family is probably a better testament of feeling towards one another than any other family would ever really have.

Matthew’s mum and uncle Des lived together for most of their lives. They were probably as close as a brother or sister could be, even in a family like Matthew’s where people would not talk much. It was Des who, in 1971, followed Jean to Manchester, as she was on her way to the only abortion clinic in the North of England. He instead insisted that they would find a way to make it work. Eventually, they found a house big enough and then lived with each other from 1986 until his uncle died in 2014.

In the sixties, women had a very defined place. They would generally work, until they were married or pregnant and then became a homemaker. Even if women had begun to train in something, or had a career, they were expected to drop that to instead become the housewife. Their role would be somewhat defined by the men around them, rather than what they wanted to do themselves. Jean was a socialite and enjoyed being out, the type of person to spend a month’s wage on a dress. This shows through a few of the images of her - though there had been a radical change after Matthew’s birth, she still had the grace and style of someone that enjoyed having some attention. In many ways, these images can begin to fulfill some sort of fantasy that she left behind in the early seventies - she has that pose down to a tee, resting her long Menthol More between her index and middle fingers as a form of statement.

With the birth of Matthew, Jean’s life was ultimately changed - she became devoted to bringing him up (probably somewhere there is the influence of a Catholic conscience with the original want for an abortion). In the sixties and seventies, women would tend to retire from working life when they married or were with a child. As Matthew says, ‘what can be achieved from a low economic background? Economics is a massive way of stopping marginalised groups’. And this is true - Jean would work full time as a cake maker, in the school holidays taking two buses up to her sisters and then two buses back to get to work.

Another body of work, Uncle, offers a portrait of Des, and Matthew’s relationship with him. There is still a slight distance there which tends to be more present with that member of the family which is not as immediate. A bond with little needed to be said, and a little bit of a boy’s club. Where his mother would cook everything, as well as clean and work every day, they would sit in front of the TV through the evenings, generally watching whatever sport was on. The interesting part of the work about his uncle is that there is that very tangible reflection of himself (at times even literally) in the images made. Where his father was absent, his uncle has presumably become that role model and form of guidance to an extent.

There is no other collective body of work that I have ever seen which can so thoroughly document the notion of family - and where most other bodies which are similar seem to fall into a purpose, Matthew’s work doesn’t. For it to not fall into a purpose seems like a criticism, when it is not at all. By continuing to make this work without the need for an end goal, the work has found its voice collected throughout the various bodies of work. If this had been shot with purpose in the sense that many projects are, there wouldn’t be the same natural observation.

During creating these bodies of work, the entire notion of the family album has changed. Now, we only keep the images that we already had, and new records remain only digital. For many they don’t even exist in a ‘physical’ digital sense - taking up space on a hard drive somewhere - instead many exist solely in the in-between. Images on messaging apps, or photos tagged in through social networks, stored by corporations rather than the self. The profound effect of this is that although we capture everything, we value much less of it. In the vast digital libraries of our phones and media, the screenshot of something we want to remember to buy is given the same binary value as photographs of our loved ones. We have gone full circle - now the only people printing images of their family again will be those devotees of the darkroom. Before the commodification of the camera in the sixties most families would have a hobbyist photographer in their midst, the archivist of the family. Now instead, we all have access to image-making though very rarely does this become physical.

Matthew’s work is deeply rooted in the photo album even though doesn’t follow a concurrent chronology. Most projects regarding family are not done in real-time - they tend to follow the format of an investigation into the past. It is this zeitgeist that sets pieces like Mother, Uncle, or Wife apart. They have been given the space for the images themselves to develop into their final forms, as opposed to an image-maker working with a developed practice and fitting this to the images being created. When he first began to show Mother around fifteen years into its making, nobody seemed to engage with it fully, and certainly did not as they do now. The traditional family album is becoming part novelty - almost an absurdity in the context of the modern use of images. In part as well it will come down to a new movement forming around these images and archives, spearheaded by Erik Kessels.

The true beauty of Matthew’s images though is not in the excellent compositions or the technical prowess. It is the beauty of the banality. Many of the images could quite happily sit in most family albums from the 80s until the 2000s and not look too out of place. It is hard to say if this is a conscious effort, or simply a reflection of photographing in this way, through the domestic space. It is precisely the non-spectacular nature of the image-making which draws you in and makes this much more accessible than most bodies of work. The images are recognisable - I’m not sure if it's because I’m also from the North of England but many of the images could quite easily be of my own family, especially grandparents and their habits and space.

In contrast, Martina was someone born into much more opportunity and the ability to do anything. She comes from a very different background - born in Prague whilst Czechoslovakia was still part of the Eastern Bloc, she was well-schooled and is well-traveled. Partly because of better connections to the EU (especially now), there seemed to be far more opportunities there than there were here. The images starkly reflect this - even if there was not initially a conscious choice, Mother is all shot within the domestic, reflective of the place of a woman in English society at the time. Wife however is consciously made with this in mind - the majority of the images are shot outside of the home. There is real freedom in Wife - perhaps because they are viewed relative to his other work - and the images carry movement through every frame.

Wife reflects a much more equal family dynamic - the beginnings of a partnership, and one which in bringing up Seb, Martina and Matthew’s son, many of the roles are equal rather than prescribed. In many ways these things are somewhat reversed - Matthew says that Martina is much more practically minded than he is (probably reflected in her independence and drive - and so she taught Seb how to ride a bike. The protective, observational, nature which is found in Mother is similarly present in Wife. In a sense, it feels not just protective of her as a person, but also a protection of a family dynamic that Matthew never had when he was growing up.

A level of engagement is lead through the work in which now the viewer is almost a part of the work. After making so many images following family and photographing them, there has to be some level of consciousness when making images that they will probably be published in the future, and does this then affect the images that are made? We, as the viewer, by engaging with Matthew’s work over such a distance of time, become a small part of that family, invested in them. The images in a sense are the visual manifestation of something beyond them, intimacy and a feeling which Matthew manages to convey.

Perhaps Matthew’s work is about family, perhaps more though it is about the aging process. Although Mother and Des trace the long-forgotten part of society - the elderly, who never really get images made of them in a positive light. Wife and Seb (working beginning around his son) look at those that are younger, subjects that are more en vogue within photography but also wider media. These individual collections of portraits are of people. Almost independent of one another. Traditionally photography about family is formulated by the grouping of them together, it focuses on the bond between people, and probably aims to photograph those absent spaces as a form. This relies on that immediacy though - that spark between people, and all too often relies on the camera becoming too much a part of the image. What Matthew is discovering though, is not family, it isn’t even really time. It is aging. It is through his works that aging is experienced, in all its different forms.

We become a part of this work. Where I mentioned first seeing the work in Derby earlier, perhaps it isn’t special because I saw it before completion. It is special because you become a part of this work and these people’s lives. Being this semi-passive observer, we are surrounded by these individuals, all of which have a closeness to the camera the same as we do with our own families. What it challenges though is something we could not, and something that Matthew cannot either, explain. It asks when your frailty becomes theirs. When do our parents - those concrete foundations upon which our formative and adult lives are built to varying degrees - when do they become weak and feeble? When do those roles reverse, and how do we cope with that?