Houses are commodities, homes are souls. Gwendraeth House is the umbrella title of an on-going, 30-year long photographic project that divines and pictures interior and exterior spaces of Peter Finnemore’s family home in Wales. This domestic space is embedded with the charge of generational memory. Where latent images are waiting to be uncovered, made visible and given concrete artistic form. Gwendraeth House is an arena to lyrically explore conscious and unconscious relationships with deep time. The home space is perceived as axis mundi, a dreaming center to divine and survey the spaces between darkness and stars. A collision, fusion and constellation of universal, primordial, historical and artistic inheritances.

JT: What was your initial motivation to start documenting your family within the setting of Gwendraeth house?

PF: The hardest question as a photographer is to ask yourself, “what do I photograph?”. The world provides an endless choice of what you can point your camera at. This choice can be overwhelming and the results often mediocre and lacking soul. For me as a student, the most interesting and emotionally rich photographs were intimate images, where the photographer has a deep relationship and a ready, unselfconscious access with the subject matter. The best examples I encountered at that time were American. Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits, Emmet Gowin’s images of his family and environment, and Roger Minick’s book - Hills of Home. These became the initial template to develop upon.

What you point your camera at, gives it value - that it’s worthy of being pictured. The setting of these images is rural Wales. Here there are margins within margins, a venn like diagram intersection of class, cultures, history and economics. Gwendreath House and its inhabitants are somewhere near the centre of that venn diagram. The project began as a psychogeographic encounter with the complex weave of forces that have shaped my identity. Photography becomes a vehicle of self-exploration and Gwendraeth House becomes a mirror to expand knowledge, identity and perception.

When I was in the US in the early 90’s I went to the Detroit Free Press and went to see their vast image library. This was before image digitization and all the images were in folders. I asked to see the images of Wales, and they got out this folder of around 7 images, the images were of sheep, castles and mining disasters, therefore pretty much stereotypical, I laughed at this… The Gwendreath House project tries to expand and renew the image bank of possibilities of the ‘welsh experience’ beyond the shorthand stereotypical clichés.

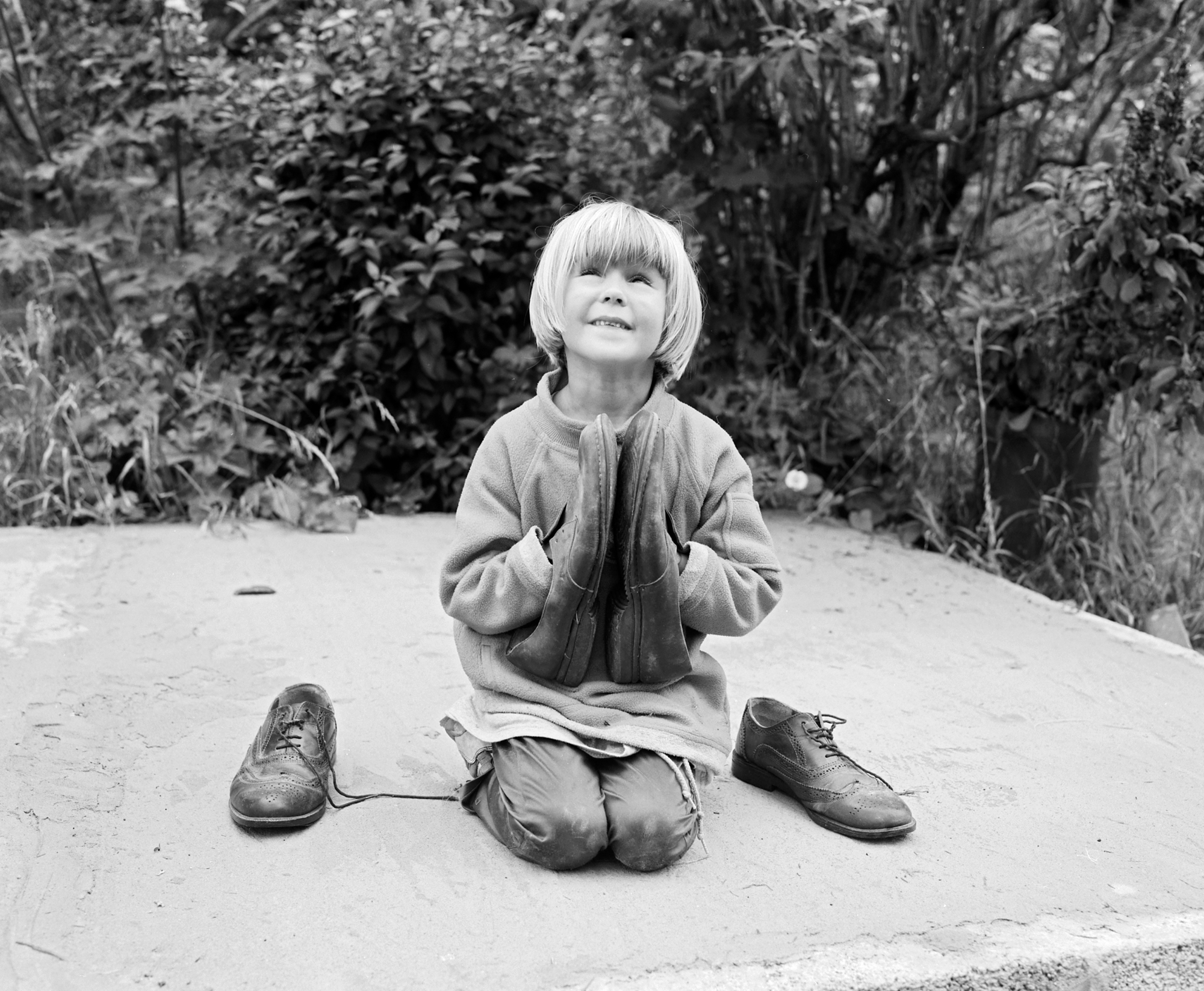

Another key motivation was to elevate the ordinary into areas of transcendence and poetic lyricism in a visual form, shifting the ground of ‘the document’ into new possibilities.

JT: Your project documents generations of conversations, actions and emotions over a 30 year period. How have you managed to keep the project so consistent for such a lengthy period of time?

PF: This project is a dialogue with the different strands of time. Personal autobiographical, historic, geographic and mythic time. In this arena of time, 30 years is not an unreasonable length and gives the project time to distil.

My approach has been Zen-like, a tightrope between control and chaos; conscious and unconscious. By allowing images to form and reveal themselves outside ego, I just simply do things and see what happens. When I was invited to represent Wales at the Venice Biennale, the curator asked me ‘so what are you going to do?’ … 'I don’t know, I just wake up in the morning and do things...'Curators do not like this kind of answer. Anyway, the work reflects a response to the ‘moment’, these moments then shape themselves into kernels of ideas, which then form into self-contained unique projects.

“Making photographs teaches you to do more photographs”, as my old teacher Thomas Joshua Cooper would keep repeating. If you are receptive to the images, the work becomes a perpetual motion machine, an infinite on-going source of imaginative possibilities. Each project chapter of Gwendraeth House is a natural evolution from the previous project. I never wanted to be a one trick pony and never settled on any particular style that I have embarked on. This can drive the gatekeepers of art crazy...I strive to be beyond categories or decades. I don’t want to be pigeonholed as an 80’s, 90’s or 00’s photographer, or a ‘welsh photographer’. I seek transcendence from categorisation and the expectations of a linear time frame. I’m currently interested in the visual dynamic passage - from image to icon. This is the territory that images exist in deep subconscious time, beyond the frame of cultural fashions.

JT: You mention that this project is a dialogue with the different strands of time. Is there any particular time that sticks out in particular over the 30 years of documenting your family?

PF: Interesting question, the answer will be mostly alien to ‘then there was us’ readers…but also addresses the plurality of overlooked cultural experiences in the UK.

In essence the work deals with a deep sense of history and its cultural echo. I think the period that had a profoundly long and enduring quality on this project, was the period of around 1904 -1905, focusing on the phenomenon of the ‘Welsh Revival’. This was a period when the Holy Spirit seemed to visit the ‘full to the brim’ churches in Wales on Sunday evenings. We had carte de visites - the ‘cut and keep’ images of the period, of those celebrity preachers who summoned up the spirit - Evan Roberts etc. This was a golden period of ‘non-conformity’ and of breaking with the established Church of England in Wales. The culture it created was specific to Wales and helped to shape an identity around Welsh language and communities. It also had many shadows - including patriarchy, hypocrisy and it was somewhat unforgiving and normalised a narrow local moral code. This is echoed in the book ‘My People’ by Caradog Evans and in some of the passages in ‘Under Milk Wood’ of characters citing their non conformist virtues of…“Thou Shalt Not” wall framed tapestries and the classic line …“ Ych y Fi.. Ych y Fi”.

Also, at the centre of this period of cultural dynamism was Lloyd George; a key Welsh influencer on the liberal direction of British politics who emerged from the Cymru Fydd (Young Wales) a movement that prompted ideas of Welsh self government.

Interestingly around this period, Sir Athur Conan Doyle came visiting our house, to talk to my great grandmother about fairies (she claims to have saved a fairie’s life from a stone throwing child). Doyle was a theosophist and I believe could have been doing research for his book - The Coming of the Fairies. Interestingly this book was inspired by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths series of photographs known as the Cottingley Fairies. These photographs are some of the most charming and imaginative made in British Photography. Indeed, their relationship to the boundaries of fact and fiction, played an important part of my artistic processes of developing a visual language of the uncanny. Collectively the Gwendraeth House project absorbs all these narratives and influences of belief, spirituality, language and cultural politics into a visual world.

JT: How do you think this experience has differed from you as the photographer to your family?

PF: I tried to work as the environment presented itself to me. It's fair to say that the family did not like being photographed and it was always a chore to get their cooperation. There was a lot of resistance and negativity, not so much about their sense of self-image, it was more about inertia and entropy (which is a key theme of the early work). Whilst in reality they did not have pressing things to do, they mostly could not be arsed… a group photo was like herding cats. This was mainly an exhausting process for me but I persevered in order to unearth these images.

In reality, this was and is a boring and fairly undramatic environment. Which does not make for good photography. I had to be proactive and creatively interact with the environment and people in order to make things happen and create interesting images. Through this hybrid mix between reportage and the set up, I tried to pilot a photographic equivalent to the literary genre of ‘magic realism’. These early work chapters were influenced by Gabriel Garcia’s book ‘Hundred Years of Solitude’.

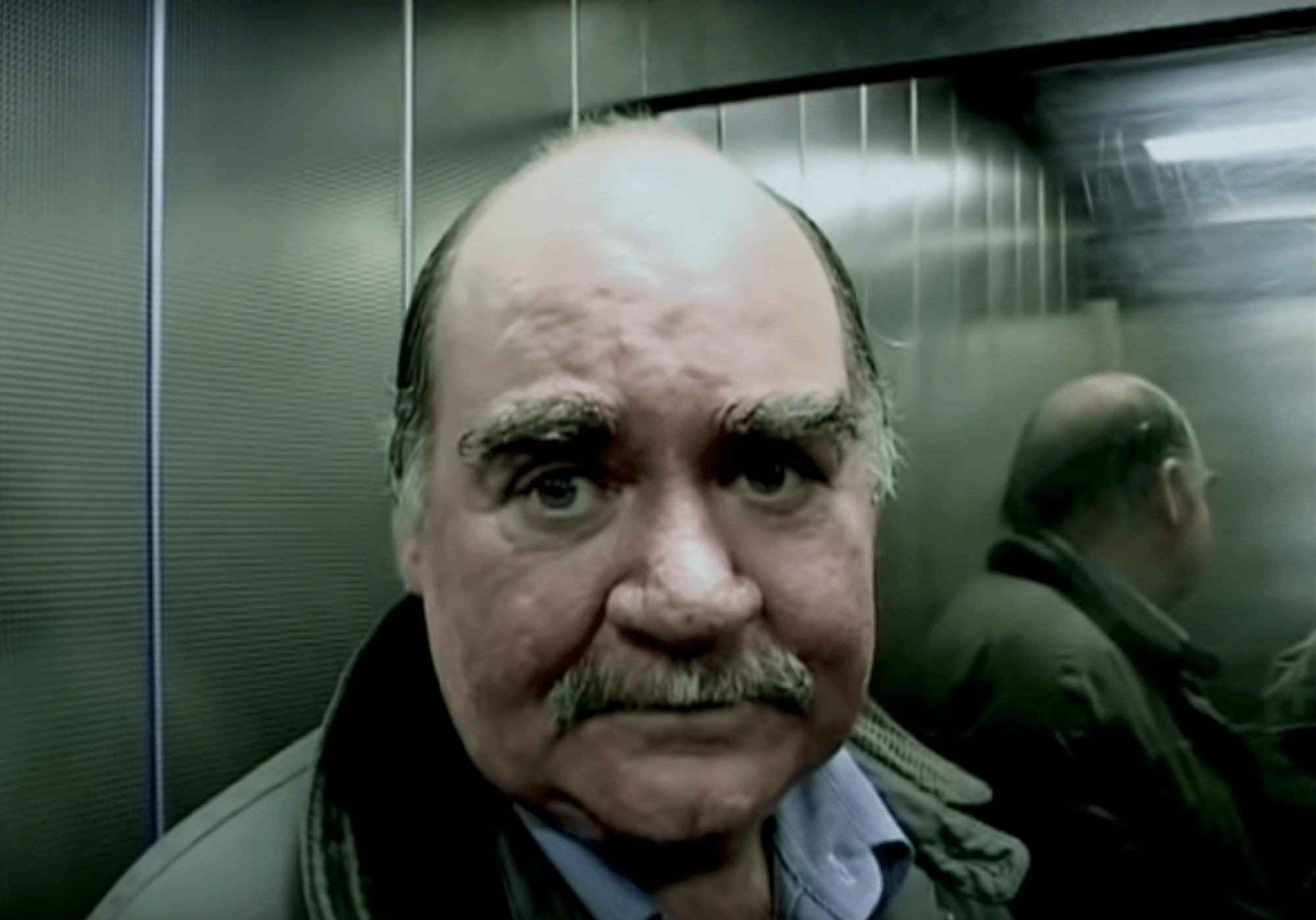

As the work developed, my grandmother enjoyed the sense of attention, my uncle readily participated in the more surreal and therapeutic aspects of the creative process and my father enjoyed that attention of being recognised as the ‘man in the photographs’ at gallery openings. He was over the moon when David Hurn struck up a conversation with him.

A different kind of photographer would have had wholly different results. I did not want a typical kitchen sink type of reportage project, in order to parade their poverty or dysfunctionalism to modernism. The images are mostly protective, but to paraphrase the last sentence of the book Hundred Years of Solitude…. ‘a family that lives a hundred years in solitude, does not get another chance, at least not on this earth’.

JT: What does family mean to you?

PF: These pandemic times have amplified family, as precious individuals that you look out for the wellbeing of. Whilst families and their interpersonal relationships can be generic, it is however, personable, a unique clan of souls. Family is a theatre of relatable shared experience, of support, joy, struggle, ease, disappointment and frustration. Their collective dynamic permeates the atmosphere of the homespace.

My extended and elderly relatives keep asking the same question annually… ‘we know that you do art and teach... but what is it that you really do, we don’t understand?’ …However frustrating, for them and me, that’s a tough existential question, what does an artist do and how it relates to the expectations of what is work and how work is perceived in society. when it gets boiled down though, what I really do is ‘to make visible’.

The other family, or tribe members of course, are the ones that you have chosen… friends… and they are equally a source of shared experience, support, joy, struggle, ease, disappointment and frustration.

JT: You must have certain memories attached to the images, what are some of your favourite shots and why?

PF: I really like the panoramic type colour image that was made on Christmas Day 1987. It has a great theatre of the absurd quality to it. It’s a totally existential snapshot image that pictures myself entering a carnivalesque family group festivity. Whilst made a few years ago, it has not become dated and still retains its pictorial magic.

I had borrowed a Pentagon camera from my student friend Richard Learoyd. It had a faulty winding mechanism, which would create overlapping images. This mechanical fault was a perfect vehicle to explore themes of time and fragmented narrative. This montage of blending different moments into one unified photographic moment has a cinematic quality. It also involved chance, serendipity and the snapshot aesthetic. Which are still recurring motifs in my photographic practice.

There is a sense of carnival in the image; of frozen family members in their Christmas hats, masks and decorative garbs. Outside and uncomfortable in the December cold. Their faces betray that they don't want to be there. They are caught in a tension of being supportive to me, my art and studies and the discomfort of being photographed. On a personal note it is also a rare image of all of us together.

Cats are also a recurring subject in my work, This exploration tries to expand the visual representation of cats. Due to the ubiquity of camera phones and digital platforms, images and videos of cats and now everywhere. There was a time when photographing cats was seen to be a no go area of lowbrow cheesiness and a total waste of film. There has always been hierarchies of subject matter; of what is considered important, worthy and valued as appropriate and serious as artistic investigation. Cats have not been one of them… cats have been depicted as details within art but never as a central dominant subject matter. The subject matter for me is always as a source of the exploration of ideas. In relation to cats, yes they are amusing and comforting companions. But they are also complex entities that occupy psychological and unconscious spaces. The cat as an animalistic hunter; the cat as a symbol and deity. Being an animal that can see in the night becomes a perfect metaphor for glimpses into a dark unconscious.

A recent powerful black and white image is ‘Dying Cat’ . This is a moody night-time interior image of my stray grey cat Smokie, (Smokie was totally grey… around 18% grey and he would also serve as a grey-card for exposure readings when making black and white photographs). Unfortunately Smokey had an underlying and incurable illness and in this image is in the process of dying in the armchair. It's a two minute exposure - which records both the sense of breathing and dissolving. The image becomes a meditation upon the process of death. Becoming formless and dissolving into a void. The edges of image, where form becomes formless.

JT: Is this series still ongoing?

PF: Parallel to this, i'm working on other projects, including an artist book of photographs made during pre pandemic trips to India. It's a complex sequence of work, which pivots around accepted genres of travel documentation and what good photography is. Let’s see if I can get a publisher for it.

But yes, I'm still working on the G House project. This is an ongoing project, still lots to do and complete. I’m working on two new chapters, one that deals with the boundaries of the garden and its relationship to the natural landscape and very atmospheric images, the other uses two old plaster walls as a backdrop as a studio setting, where I compose anthropomorphic tree stumps into strange arrangements. These seem to be psychically charged and totally weird...

I’m also expanding the project chapter - Lesson 56 Wales, into Lesson 56 - 59 This deals with family home / memory / school books / artefacts etc in relation to deep colonial history. In the style of the Chris Marker film La Jetee, this is composed of still images and sound. To bring it up to date I will include brexit type visual material into this ongoing journey with history. A version of this film is on my Vimeo site.

As Gwendraeth House is biographical and my mother is German (my father met her during national service in Berlin in the 50’s … he was at Spandau Prison guarding Rudolph Hess (Hitlers 2nd in command))... I want to create a new body of work dealing with that cold war period - I’ve got the materials and ideas that I want to use, so that’s in the pipeline of things to do when I have the time and focus…

JT: When do you think the project will come to an end, if ever?

PF: The project has developed its own momentum and obsessive passion, it’s like a combination of a perpetual motion machine and Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo.

The more you work and think about a subject, you begin to find ways to draw upon authenticity and meaning into the images. The well of picture making gets deeper and potentially endless, as long as the dynamic creative energy and motivation is there.

Also, I think it's important to point out the idea of ‘old work’... unthinking creative industry and educational types etc.. always seem to be fixated on “ what's new, what new things are you doing“... impatiently wanting to jump onto another project, always focusing on this new future thing, as if previous images or work do not contain the same value. Or that it is deemed “finished”. You might have just finished a complex three year body of work and the question they immediately ask is what new things are you working on. This bullshit non-thinking response drives me fucking crazy !! ‘Old’ (for the want of a better word…) materials can be renewed, repositioned and made contemporary and relevant in many curatorial ways. Maybe a more nuanced approach to materials and creative possibilities define artists from photographers.