Currently based in New York, Kaitlin Maxwell received her BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 2016 and pursued an MFA from Yale School of Art in 2019. Mainly focusing on documentary based projects, Kaitlin’s long-term series encompasses themes of relationship and family. She dissects her life through her images to try and understand who she is and where she originates. With a particular focus on natural light, which often acts as a broad character subject itself, she analyses the intimate ways in which people close to her interact with themselves and the world. Kaitlin is fascinated by the human condition. Her work seeks to understand and interact with this concept of how we navigate our uniquely challenging ways of being. Her work acts as a window into her life and an encapsulation of her attempt at dissecting the issues of self-reflection, identity, sexuality, femininity, and objectification. She aims to share her own experience of doing so with the world.

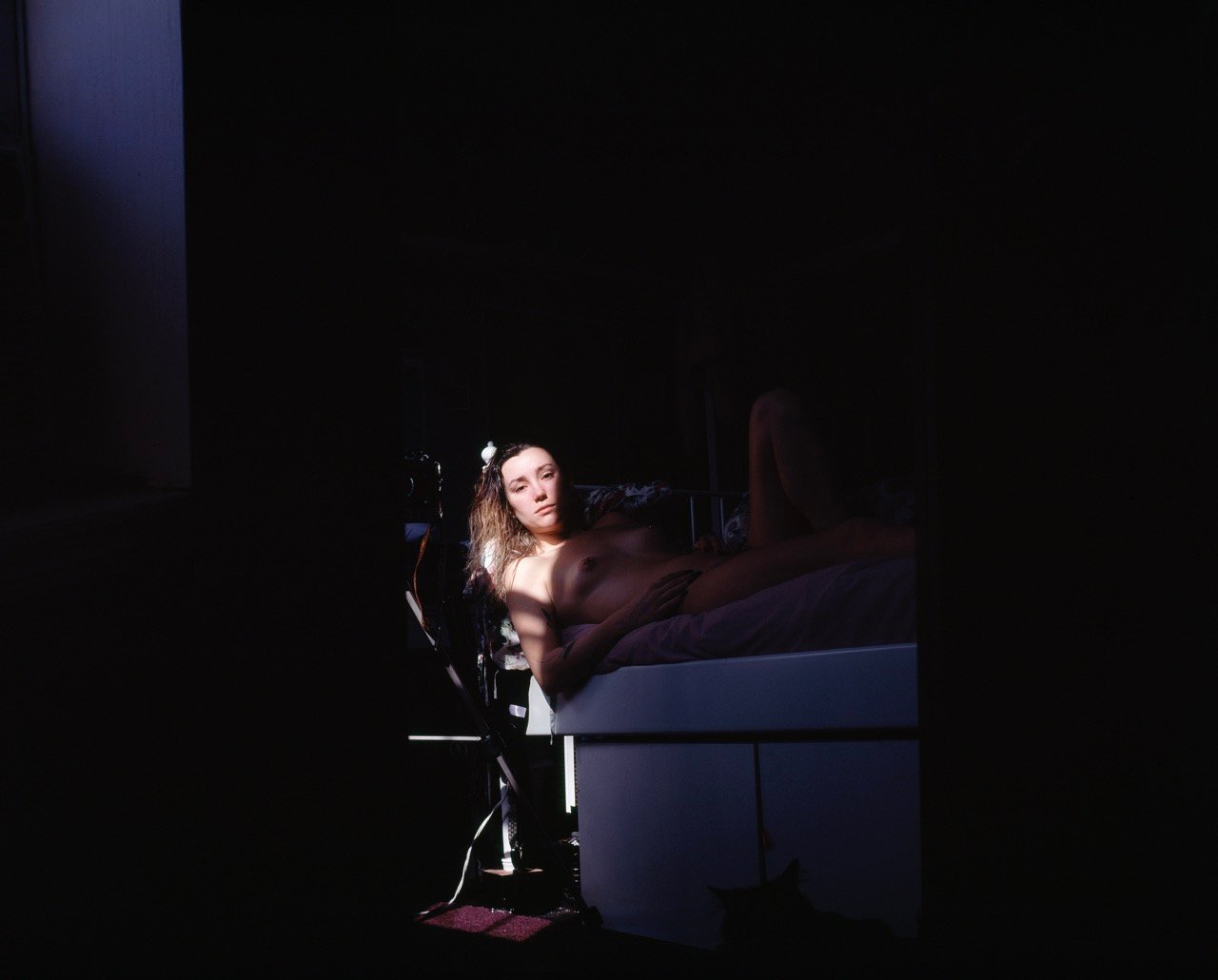

In order to explore and better understand the dynamic that is created between individuals in complex and layered relationships, of any kind, I began photographing the ones who were closest to me. As I began dissecting my own relationship with my mother and grandmother, a catalyst began to occur and I found myself questioning if, I too, was capable of possessing the qualities I have always admired of the women who preceded me. In making these images, I am focusing on examining matriarchal figures in my life, which has left me realising that there is so much more to my identity than I am aware of. By allowing the experiences of my reality to dictate my perspective, I have found myself immersed in an ongoing journey of self-exploration, highlighting themes of femininity, intimacy, objectification, and sexuality. – Kaitlin Maxwell.

I am quite curious about how your dissection of the relationships between your mother, grandma and you first began — other than photographically? More specifically, I am curious whether you started looking at the relationship between your mother and grandmother or did it perhaps root with you first?

Growing up, my mother and grandmother have always shared a really close and intimate dynamic with one another. Really my mother, grandmother and grandfather have always had a unique bond. I thought it was a kind of closeness that everyone had within their familial relationships until I got older and realised how truly special and different it was. My mother always says that her father taught her how to love which then allowed her to teach me how to love and that’s something that I’ve always found really powerful. I initially set out to try and understand this parent/child relationship with my mother and grandmother, as a means to try and grasp this level of human connection. I lost my father when I was young, so I feel that a large part of my affinity and obsession with analysing their connection so closely, and mine as well, stems from this relationship in my life that is physically inaccessible and unable to be explored in such a way. I believe my father’s absence is one of the biggest subjects within my work and where my exploration has stemmed from.

I am also interested about how your relationships were before this project had began. I am aware that mother-daughter relationships can be incredibly communicative but also at other times, incredibly nonverbal and intuitive. I wonder if through this exploration, your relationships began to get deeper as a result. I find that photography can have so many functions, one of them being to tell a story but perhaps at other times, to be a gentle way to create more depth in our relationship with the subjects we choose.

As this series has progressed over the last 5 years, it has opened up my relationship with my mother and grandmother in a way that wouldn’t have been accessible if this work hadn’t been made. The act of collaboration that occurs throughout the image making process is so intimate and being able to closely observe them through the camera has unveiled levels of vulnerability that I was unable to see before. Peeling back these layers and working through the challenges of discomfort that you are confronted with when in front of the camera, has allowed the three of us to develop our own visual language together. When I look through the photographs of my mother, grandmother, and myself, I can see conversations being translated out from the images of things we may have not communicated verbally. Whether it’s a portrait or an image of an act of care being done, I can see through this look or action something I wasn’t able to fully understand before. I’m not sure if this makes sense, but ultimately, I can feel the three of us expressing things to each other through my photographs that are not said verbally. The three of us actually joke about our ability to telepathically speak to one another and I feel this is a direct result of us collaborating together through this work.

When I read your introduction to the project on your website I wondered about your use of words, especially when you say “possessing the qualities” about yourself in relation to your mum and candy. Could you speak more about the qualities you saw? I wonder, did you not think you had those qualities before and did you, through your exploration, realise you do possess those qualities?

I’ve always really admired the way in which my mother and grandmother exude femininity. I think I’ve always had a difficult time feeling confident with embracing my own idea of femininity and watching the way the two of them seem to navigate the world with such confidence in themselves and their bodies is something I’ve always found to be really striking and powerful. They are two extremely strong women and I constantly found myself wondering if I’d ever measure up to them. This is why self-portraiture is such a big part of my work. I wanted to document performances of my own understanding of gender in order to further examine who I am. I don’t feel that I’ve fully reached a point of whether or not I possess these qualities because I’m not even sure if I look at myself or the construct of gender in this way anymore. Making this work has pushed me so far outside of what I’ve ever been comfortable to do and also made me realise that my ideas of femininity weren’t as dynamic and complex as they should be. As a woman, I felt pressured to categorise myself into a sector of femininity that I believed to exist. I wasn’t sexy enough, or girly enough, and I never quite understood where I landed. Art is one of the most important tools for learning and unlearning ideas we assume to be inherent or innate in our thinking, and this entire series has been a very important part of that unlearning process for me. Through making this work, I’ve been able to unlearn the patriarchal ideas of gender that had been pressured and put upon me since I was a young girl, and that in itself has been one of the most exhilarating aspects of being an artist. Not only have I been able to challenge myself and my understanding of societal, normative ideals, but I have been able to do this through the making of photographs of my mother and grandmother. In understanding the complex nature of their history as individuals, the two of them have taught me how to unlearn. Challenging you and helping you grow are some of the most powerful things someone can do for you and these are the qualities I wish to possess.

If you compare yourself to when you started the project to the now, do you find that you’ve gained new strength within yourself that was independent of your relationships? Or does it come with them?

The strength I’ve gained from this project is simultaneously independent of these relationships and cultivated from them. It’s something that was there and continues to be, but I didn’t realise existed until I began making this work. Through deeply analysing my mother and grandmother’s strength and courage, I was able to uncover that within myself. I was so clearly able to see these things in them that I admired, that it wasn’t until I obsessively focused on what I didn’t see within myself, that I realised how different my perception of self was. I realised I was looking at myself differently and this realisation created a new type of strength that wasn’t there before. It’s a type of strength that came to fruition through self-exploration.

Could you talk about Florida, Indiana and Connecticut? I notice that there were many photographs taken in these three places throughout your project.

I was born and raised in South Florida which is why this space occupies a large part of my work. My mother and grandmother still live there, and I go back as often as I can to make work. The harsh light and colour palette of Florida is something I’ve always found really beautiful and striking. The way the sunlight interacts with skin and how the bright colours and foliage come together to create an ethereal, almost magical world is something I’m constantly playing with. Grandma Candy is originally from Indiana, as well as my mother, and they relocated to South Florida in the late 80’s. My grandparents still have a home and family there, so some of my work has been made on my trips back to visit. I used to go to Indiana every year as a child and it was almost a home away from home for me. It’s a place where I feel my grandmother and mother are able to tap into an earlier version of themselves. I hope to make more work here with my Grandmother. Her and my grandfather bought a house in the small town of Kokomo, Indiana where they met when they were 12 years old. My grandfather passed away at the end of January of this year and I feel that this home will be a much larger presence within this work in the years to come. Connecticut is a place that holds less sentimental value to the work comparatively. I was living there for two years while attending graduate school and my family would come and visit for holidays. Considering I didn’t get to see them as often as I wanted, I would maximise every opportunity I had to make work with them.

I’m interested to know the idea behind being, at times, in the same clothes? It felt like an effort to feel what it feels like to be the other people you’re documenting.

In essence, that’s exactly what I am trying to do. One day grandma Candy and I were making photographs and she brought out her old clothes to show them to me and we both started putting them on and I felt like a child again. I used to play dress-up when I was younger, and all of that wander and child-like innocence came back to me in that moment. It was a confusing feeling because I hadn’t felt that type of innocence and freeness in so long, but it was also accompanied by new feelings of self-consciousness and whether or not my body looked the same in her clothes as she did. I thought if I wore her clothes and performed for the camera, I would be able to exude all those things I admired in her. I think of these photographs as performances. I’m acting as myself, acting as someone else. At first, I thought I was dressing up as her in order to try and be her, but as I kept making these images I realised that I was putting on her clothes in an attempt to escape my own insecurities and discover a different version or part of myself.

I wonder if you father’s absence in your life has actually created a presence in your photographs – what do you think? If he was with you, how do you think he would play a part in this project?

This is something I think about constantly with my work. I think my father’s absence carries a huge presence in my work and is one of the biggest subjects within it. I’ve always been so fascinated by the idea of absence carrying the heaviest weight within a piece or body of work. One of the most challenging things to do as an artist is to create work that says what you’re trying to say without blatantly saying it. The empty spaces and the voids between are my fathers presence. The viewer is absorbing this existence without even realising and that’s so powerful to me. It’s like the spaces between sentences in a novel, the reader is creating something they don’t even realise. Or even in Chris Marker’s La Jetée for example, one of the most compelling aspects of this, to me, is the space between the stills. There’s a world, or a character, or a presence that exists within this liminal space that we may not even realise is there. I feel that if my father was physically here with me, I may not even have discovered art in such an intimate way. After he passed, making art was cathartic for me and I found something that helped me process the grief and trauma I was experiencing. Honestly, I still feel very much the same about making art today as I did 13 years ago after my fathers death. It’s the one thing I’ve always used in order to understand my existence and my experience.

I wonder, from all of the things you’ve learnt about yourself and your relationships with these important people in your life, what is the single most important thing to pass down to younger generations in your family?

The most important thing I’ve learned from making this work is being able to trust myself and my intuition. This project has been, and continues to be, really challenging and I’ve learned that one of the most valuable aspects of being an artist and a person, is having the ability to completely trust yourself. It’s easy to become unsure and create work that you don’t feel is representative of who you are or what your vision is. You find yourself making work that you think people want to see. At times I found myself falling into that trap and I was unhappy with what I was creating. I didn’t become an artist to make work for other people. I became one to better understand who I was, and I had to remind myself of that. I make work now because I feel that it’s what I need to make. I wouldn’t have gathered the courage to listen to myself had I not made mistakes along the way, and I’m really grateful for that. I hope the younger generations in my family, or others, can relate to my work one day and see that they have the ability to listen to themselves too.