Jonathan Moore is a photographer driven by the same restless curiosity and commitment to cultural understanding as the documentary photographers we are taught about. A self-taught photographer based in London, his work evokes the images that come to mind when you think of photography at its most iconic, images made by those who place themselves in situations others would never consider, in places far beyond the reach of the internet.

In recent years, Moore has fully immersed himself in his practise, travelling extensively to create bodies of work that offer rare and intimate glimpses into unfamiliar worlds. In 2021, he packed his bags and travelled to Georgia, beginning a journey that has since taken him through Ukraine, India, Bangladesh, and beyond. Through these travels, Moore continues to build a compelling visual record of moments, guided by patience, presence, and a deep respect for the cultures he encounters. We got to sit down with Jonathan and discuss two of his projects, Melted into Steel and Ijtema.

The last time we saw each other was in London a few years back and we spoke in detail about your passion for photojournalism. Since then you’ve been away in many parts of the world using documentary photography as a method to document your journey. Can you tell me how this journey has been so far?

It’s been many things at different times but overall it’s been enlightening, illuminating and very humbling. I’m very lucky that I don’t rely exclusively on photography for my income. I came to photography relatively late and used to work in policy for a mental health charity. I now work in policy on a freelance basis alongside my photography and all I need is an internet connection. I used to think the only way I could fund my photography projects was if someone paid me, but the last few years have completely changed that. I can be anywhere and I feel very lucky.

Your work across these countries engages with a wide range of themes. What has drawn you to these places and the themes within your work?

I’m always drawn to things that are misunderstood, ignored, or on the edges of society. It’s important to me to keep learning and it’s as much about what I experience as a human being as it is as a photographer. I think I do better work when my heart beats faster. It means a lot to me to be trusted by the people I photograph. So I research where in the world I might find all these things and then I go. Not everything I have attempted has worked, but even then I’m glad I tried. The things that have worked will stay with me forever.

Is there a particular message or idea you hope to communicate to the viewer through your photography?

I don’t see it as part of my job to get a message across. I am the conduit for whatever is happening in front of me. In projects where I develop more personal relationships with people, my aim is to make them comfortable enough to behave like I am not there. In more fleeting or chaotic moments where that doesn’t apply, I want to make pictures that show how it feels at that moment in time. Any message a viewer feels when they look at my work comes from the people or place in the frame. Whatever matters to me is showing how something is, not how I feel about it.

Looking at two of your projects (Melted into Steel and Ijtema), it’s interesting to me how the works created in Ukraine and Bangladesh reflect contrasting global contexts, from the ongoing war in Ukraine to the peaceful religious gathering of Bishwa Ijtema in Bangladesh. What do these events suggest about differences in how communities around the world come together?

One thing that travel and photography have shown me is the lengths that people are willing to go to for one another. Political discourse is becoming increasingly violent in the UK and around the world. The people who tell us that this religion hates us, or that nationality can’t be trusted, do it because it serves their own interest. The reality is very different.

In Ukraine I met people who had had their homes destroyed and said goodbye to their families at the border and immediately started volunteering for 16 hours a day. At Bishwa Itjema people with virtually nothing would give the little they had to help others less fortunate.

The circumstances in Ukraine and Bangladesh were very different - one being shaped by a will to survive, the other by a shared love of god - but that kindness is something people of all backgrounds are capable of. Where you are from and what you believe are irrelevant.

You mentioned that you may return to Ukraine soon. Looking back now, knowing that the situation continues three years on, it feels deeply emotional. Returning to photograph there again would look different, wouldn’t it?

It definitely would. I don't think those same photos would be there anymore. What defined the first year after Russia invaded Ukraine was the immediacy of the threat and the uncertainty that brought. The country was in a constant state of flux and nobody knew what would come next.

Certainly in the centre and west of the country, things have fallen into more of a pattern. I visited Kyiv briefly at the end of 2023 and things felt very different. There are still regular air alarms and frequent attacks by missile or drone, but a degree of normality has returned.

On one hand that is a sign of Ukraine’s success, but on the other I have friends who are serving or have served that feel some people are trying to pretend the war isn’t happening, and they’re only able to do that because of the sacrifices soldiers are making on the frontline. In any case when I went back the atmosphere had changed and it didn’t feel like pictures were there for me in the same way on a day to day basis.

The east of the country is very different and there is still work that I want to do. It will just take a lot more time and planning than I can give right now.

How would you describe the importance of Bishwa Ijtema to those who participate in it and did your understanding of the event change after experiencing it firsthand? If so, how?

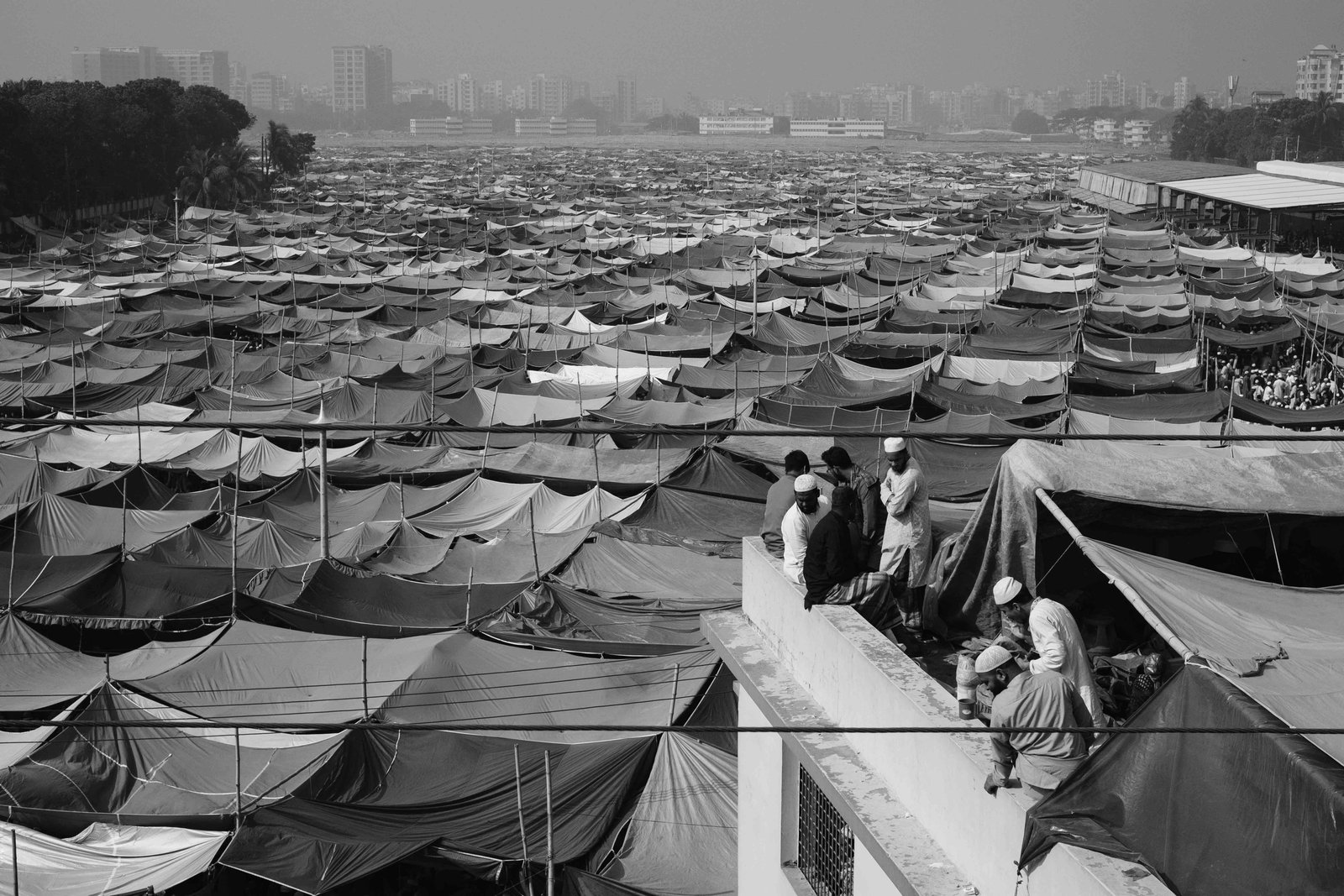

It’s the second largest Muslim festival behind the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Millions of people come to Dhaka for Bishwa Ijtema every year, but it is far less well known. Its focus is calling for world peace.

I didn’t know a huge amount beyond that beforehand. I saw the videos and pictures of the huge crowds and knew it was something I wanted to photograph and experience. I had been to Bangladesh before and confirmed with a local friend that it would be ok for me as a non-muslim to attend. Then I went.

The thing I had never experienced before was just how much a belief in God can move people. Bishwa Itjema ends in a huge prayer for world peace where everyone kneels.

The festival takes place on the edges of Dhaka, but the last prayer is broadcast through speakers all over the city, and everything stops. I saw so many people in floods of tears during that prayer. It was totally silent apart from the sound of the prayer echoing around the city. It was one of the most powerful and moving experiences of my life.

How did you build trust and gain access to capture such intimate moments of worship and community?

I think the first thing is that I never hide my intent. I wear my cameras openly on my shoulder. Crowds or wide shots are different, but don’t take pictures of people directly or at close range without their permission. This is often just a smile, a nod to my camera, and then to them. I always try to be respectful of the environment I’m in and I hope people see that. This is more about a feeling than following any rules: when to move or be still, when not to take a picture.

At Bishwa Itjema I didn’t see another white person, so many of the people there were as interested in me as I was in them. I can’t stand selfies but I posed with people for hundreds of them at Bishwa Itjema. I think that was a fair exchange.

Which photograph from the project is the most meaningful to you, and why?

I think of the picture where I am between two trains and people are climbing onto the roofs of the carriages. I remember watching footage of people doing that at a Bishwa Itjema from years ago during a particularly dark day in one of the covid lockdowns and thinking how much I wanted to be there. So being in the middle of it was a full circle moment for me.

Were there particular moments that deeply affected you as a photographer or as a person?

My experiences in Ukraine after the invasion definitely changed my view of what nationalism can mean. Until then I had always seen it as something that divided people or gave a sense of superiority over others, which in many cases I still believe is true. But in those first few weeks and months nationalism was what brought people together. It wasn’t about superiority, it was about coming together to survive. If it wasn’t for nationalism, Ukraine would no longer exist.