Pehlwani, also known as Kushti, is a traditional form of wrestling practiced across the Indian subcontinent. The sport took shape during the Mughal Empire, evolving through a fusion of Persian Koshti Pahlevani and the ancient Indian wrestling tradition of Malla-yuddha. Over centuries, Pehlwani has grown into a discipline that is not only a test of physical strength and endurance, but also a way of life rooted in ritual, discipline, and cultural heritage.

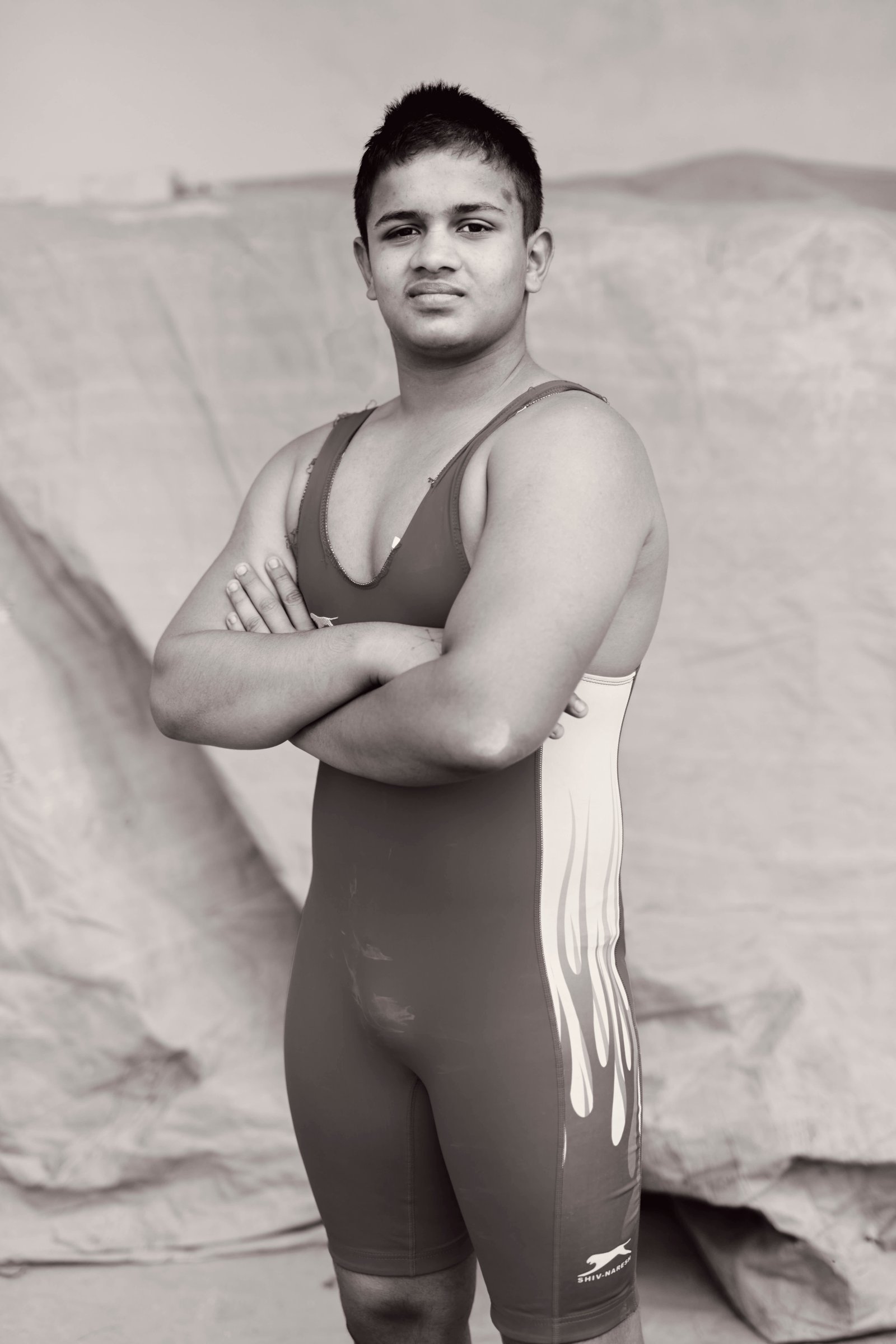

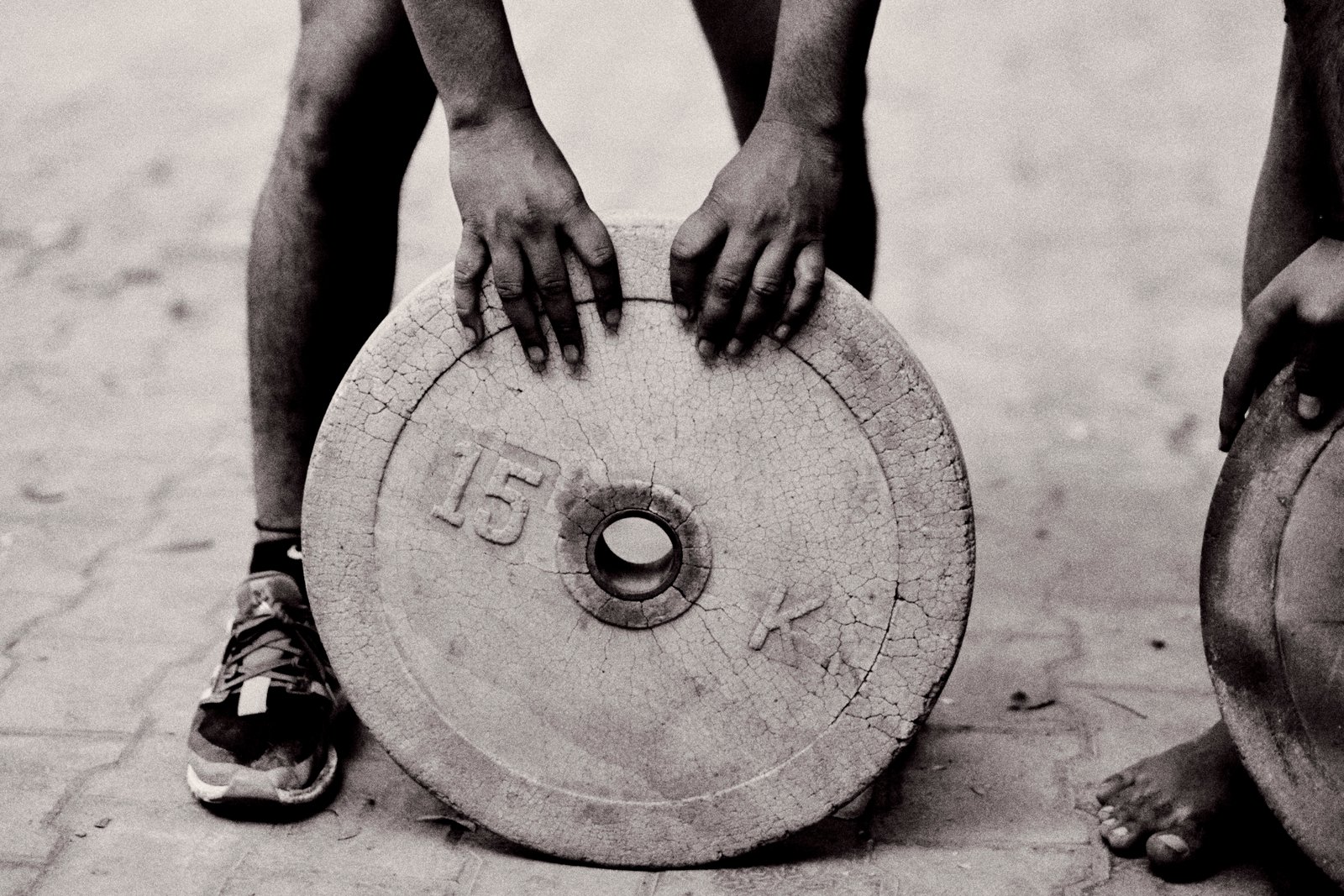

Typically practiced in earthen wrestling pits known as akharas, Pehlwani emphasises rigorous training routines, strict dietary practices, and a deep respect for one’s guru and fellow wrestlers. Wrestlers, or pehlwans, often begin training at a young age, committing themselves to years of physical conditioning.

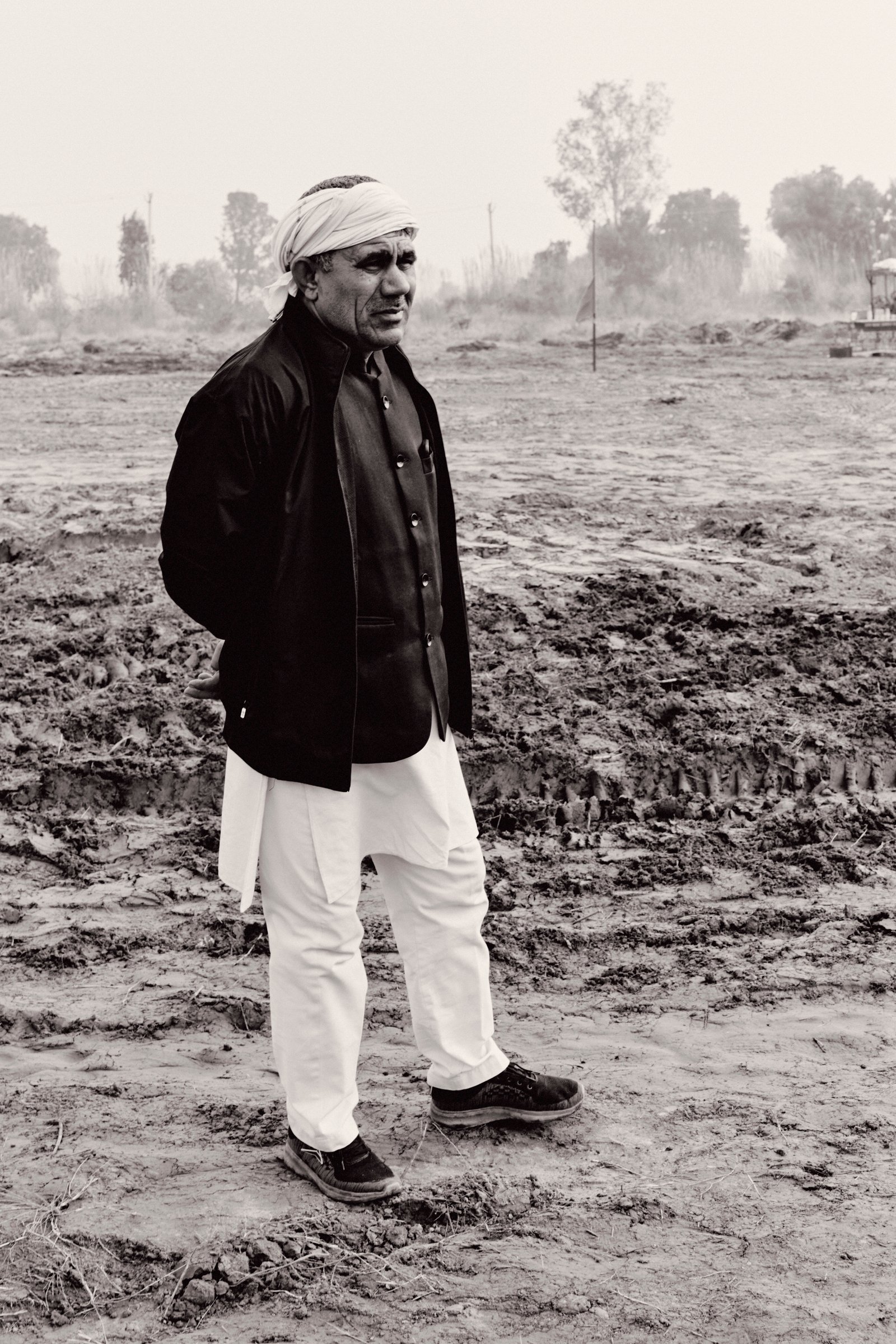

Photographer Robert Palmer traveled throughout India to document this enduring sport, capturing both the intensity of the bouts and the quieter moments of daily training and devotion within the akharas. During his journey, he spoke with Karan Puri Goswami, a professional athlete deeply involved with Kushti, who shared insights into the sport’s history and his relationship with the sport.

Karan’s introduction to Kushti came through his grandfather, the man who planted the seeds of wrestling in their district. “When my grandfather was just twelve or thirteen, he ran away from home to earn money,” Karan explains. “He went to Delhi, where he saw Akharas and learned traditional wrestling in Haryana. When he returned, he brought wrestling back to our city, to his friends, and to our family. That’s where everything started.”

Wrestling has been central to Karan’s family for generations, beginning with his grandfather, who introduced the sport to their village. Growing up, Karan was surrounded by wrestling and recalls watching his father train from an early age. With an Akhara in their town and a strong family identity rooted in the sport, wrestling became more than a pastime, it was a family tradition. Encouraged by both his grandfather and father to continue this legacy, Karan began training seriously at the age of fifteen, once his studies allowed him the time to commit.

“When my grandfather started wrestling, we had no name in society. All of that recognition came from him. My father became a national champion. My uncles continued. Now I am continuing. We are known as a wrestling family. But sports don't run on nepotism. You must earn it. If I want to continue my grandfather’s legacy, I must work for it.”

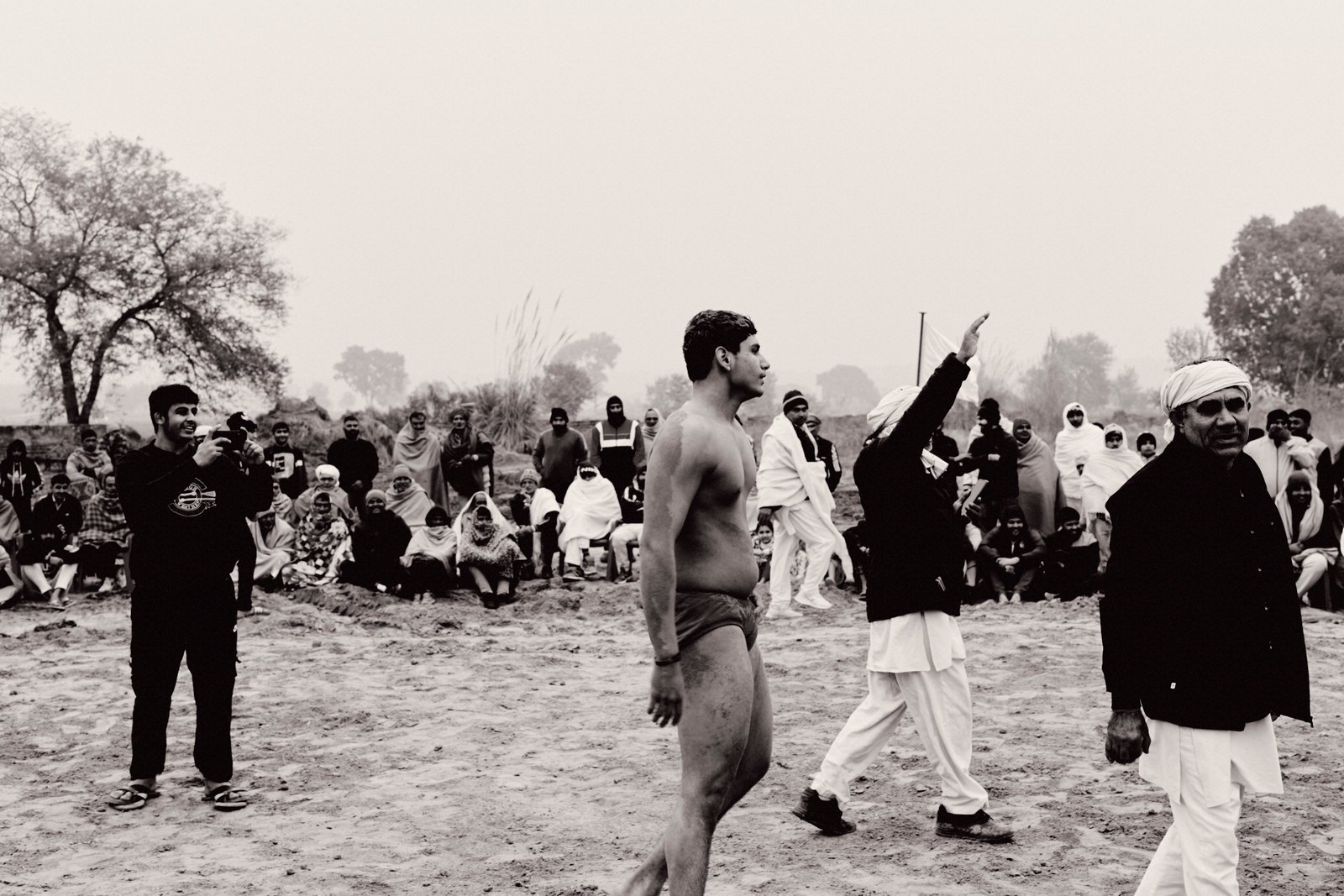

Akharas serve not only as training grounds but as living environments for many young wrestlers. Students often stay there for years at a time. Boys start training as young as nine or ten to later become professional wrestlers.

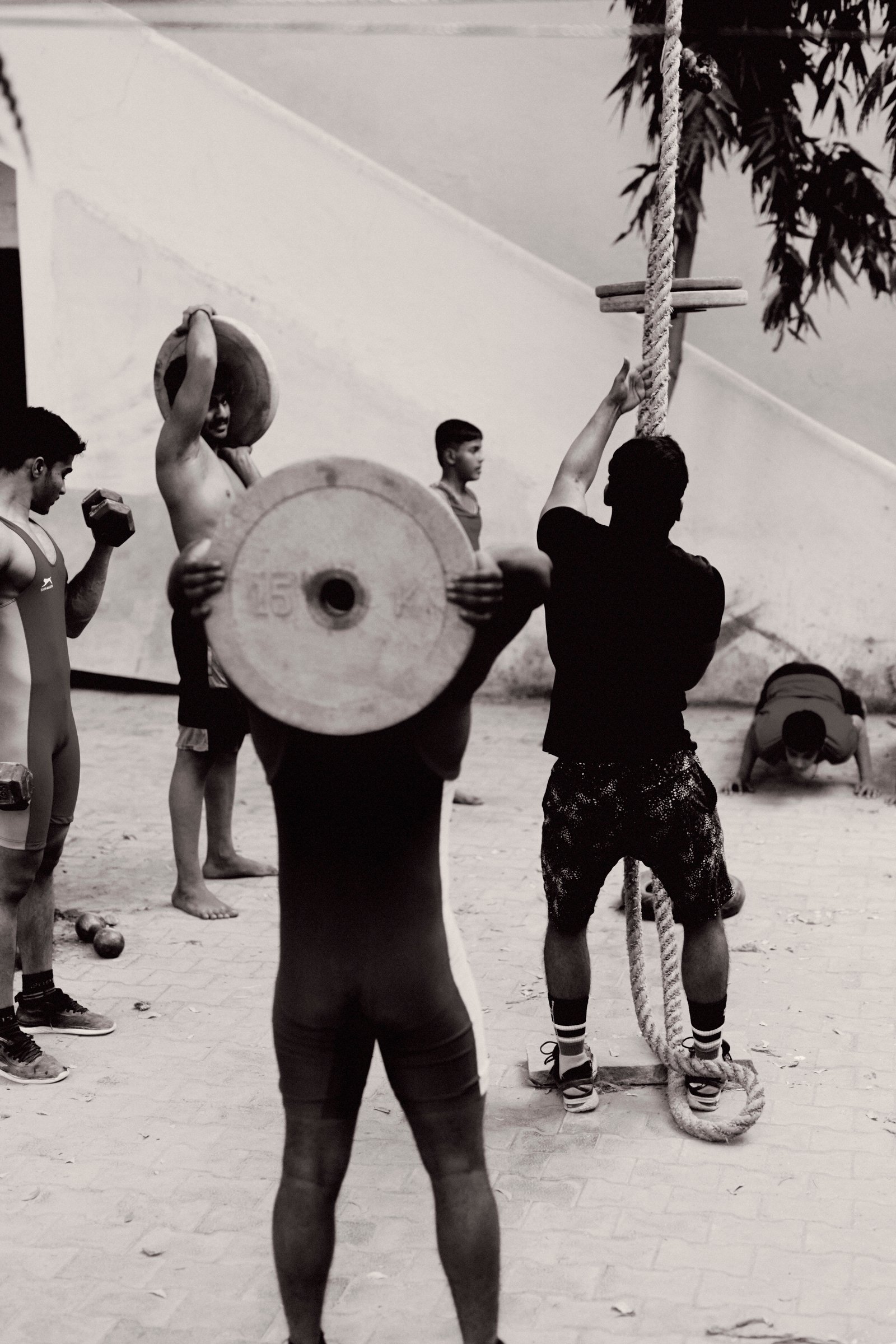

“When students live inside the Akhara, they become more disciplined,” Karan says. “Outside, there are distractions like friends, family, phones, television. But in the Akhara, the entire day is scheduled. They must follow that routine.”

“They wake up at 4:30 in the morning. Morning training lasts two and a half to three and a half hours. If they are school-aged, they attend school afterward. Around noon they return, eat lunch, and rest. Then evening training starts around four and goes until eight, sometimes later if they are preparing for competitions. After dinner, they study and rest. Then it repeats.”

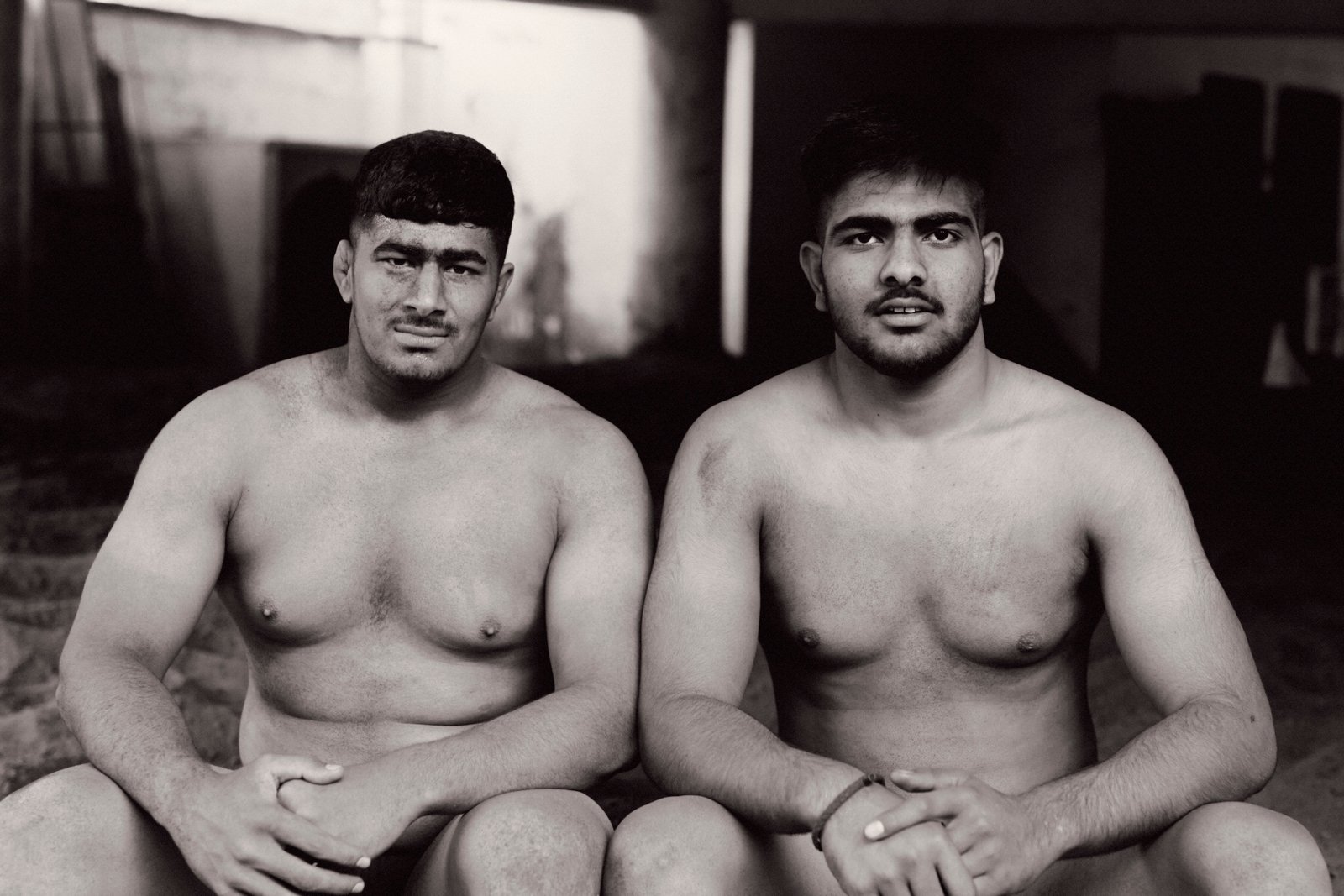

Trainees usually remain in the Akhara year-round, leaving only for exams or brief holidays. Some stay for as little as two or three years; others remain for much longer. The Akhara, Karan says, becomes a second family.

At the heart of the Akhara system is the relationship between coach and student. “There must be boundaries,” Karan explains. “The coach should be open, but not so friendly that the wrestler stops taking him seriously. Respect is essential. At the same time, the student must feel free to talk about any problem.”

“In India we call the teacher ‘Guru.’ The relationship becomes stronger with time. Many trainees live with us for six or seven years. They become family. It’s a lifetime bond.”

For Karan, as a professional wrestler, winning is important, but aside from that Kushti means so much more to him.

“Wrestling teaches discipline in life first, sport second. Medals should be secondary. If we cannot make a good human being, then there is no use for medals. The early mornings, the strict routines, the constant training, these shape more than athletic ability."

“They learn respect for elders, brotherhood with teammates, and how to work hard consistently. These values stay with them in their family life, studies, and careers.”

Today, Kushti continues to evolve. India has transitioned from mud wrestling to international mat wrestling, with new forms such as beach wrestling growing in popularity. In recent years, women have also been central to the sport, with Sakshi Malik earning a bronze medal for India in the Olympics. A professional wrestling league is set to relaunch this year, reflecting the sport’s expanding future.